Auction > Past > Haus Gallery

Haus Gallery 07.05.2023 13:44

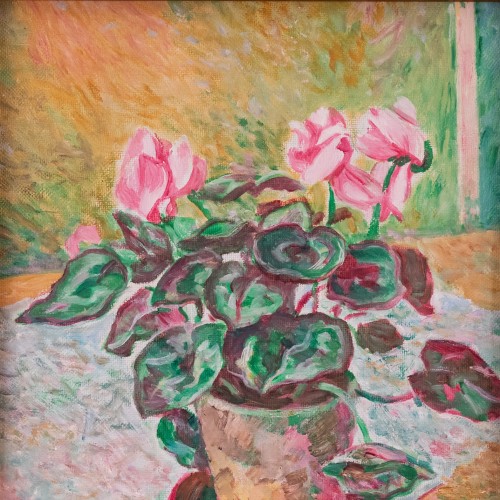

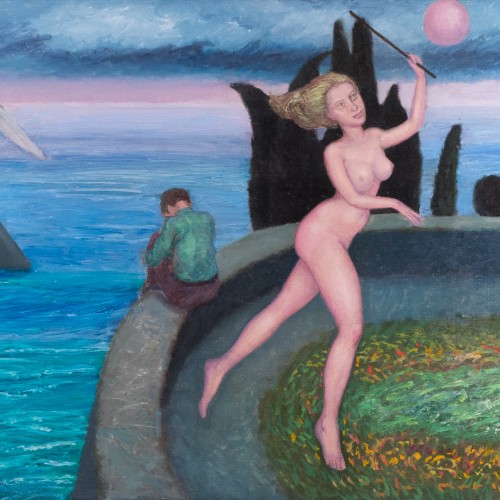

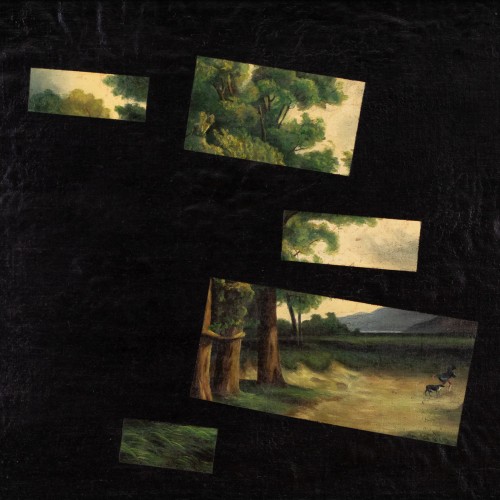

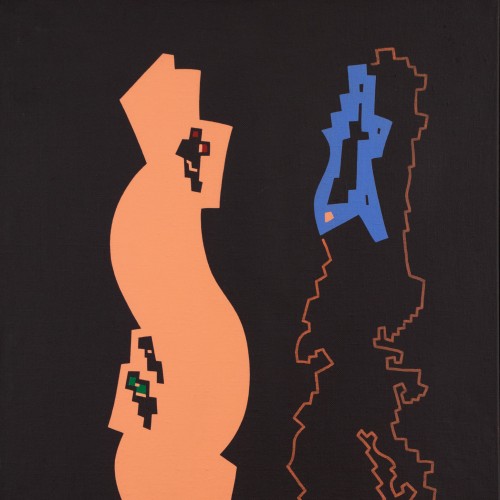

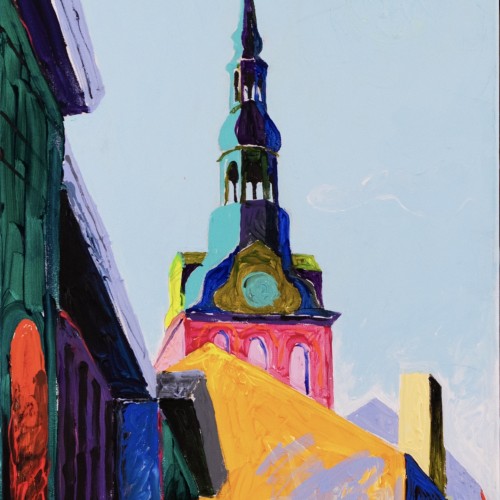

ESTONIAN ART AUCTION - 1966 TO PRESENT

SPRING 2023

Sunday, 7th of May

IN MODERN AND OLD-FASHIONED WAYS

Foreword: Piia Ausman, Curator of the Auction

Author of the catalogue texts: Heie Marie Treier, Art Historian (TLU/BFM)

The 2023 spring auction organised by Haus Gallery draws art history on a timeline. While our auction catalogues of the past few years divided the works into thematic groups according to motif, nature or unity of thought, this time we are moving clearly in time and chronology. The works are divided into chapters by decade, highlighting what is important and distinctive, illustrated by each individual work in that decade. For us, it is important to leave an educational mark on each auction, which pretends to be a comprehensive group exhibition of a certain era, both on the gallery walls and in the catalogue – material that can be used later on to further one’s knowledge of art, and which looks at both general artistic trends and each individual work.

The starting point for this catalogue is 1966. The 1960s more broadly were significant in our art, as there was a very clear mixing of the younger and older generations, with some coming in new and discovering, trying to grasp the world art trends behind the Iron Curtain without having the opportunity to leave the closed space of the Soviet Union, and others, many of whom continued to create in a remarkably innovative way, but whose years of study, mostly at the Pallas School of Art, were intertwined with the experience of France, Germany, and the rest of Europe in the early decades of the 20th century. This is how legendary abstract art exhibition by Elmar Kits took place in Tartu in 1966, which was reconstructed in 2016 and whose curator Peeter Talvistu writes the foreword below: ‘Elmar Kits (1913–1972) is considered one of the most outstanding and prolific creators in Estonian art history. His 1966 solo exhibition, most of the 105 works of which were completed in the same year, was the first real triumph of abstract art in Estonia and one of the most important milestones of the artistic revival of the late 1960s. The 1994 catalogue of Kits writes about the exhibition: ‘This exhibition can be considered a manifestation of modern art and a highlight of the 1960s.’’

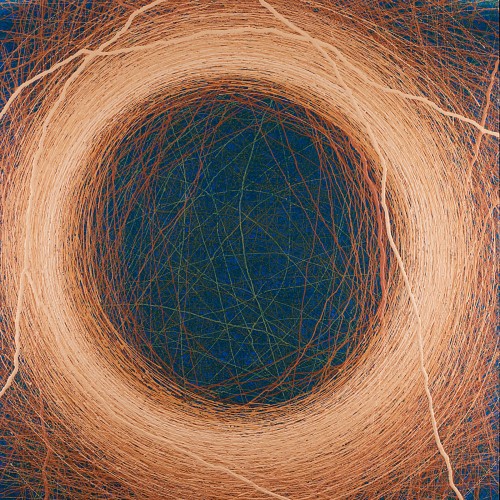

Respecting this important point in the history of art, Haus Gallery drew a line between the two 2023 spring auctions to mark a culmination of the comparison between our older and younger artists, when some were still teachers of others. Later on, especially through the eyes of the art of the 1990s, this moment of the 1960s would seem to have been forgotten in retrospect. At that time, conceptual art was already dominant, experimenting with large-scale paintings and installations and art with a distinctly social undertone, and for this generation, the Soviet past was less looked at. Dizzying progress was made, and the Pallasian format remained distant and chamber-like, whose impetus, effectiveness and, in fact, the freshness of the 1960s is something we are rediscovering in our own way to this day. However, when we talk about the art of the late 20th century, we cannot ignore the continuation of a more intimate style of painting and more traditional and realistic art, of which the auction selection offers examples. This catalogue encapsulates in a concentrated and expressive way precisely what began in our art in the second half of the 1960s, became hyper-real in the 1970s, became intriguing in the early 1990s, and expanded with the possibilities of artistic freedom in the era of independence up to the present day. So, in the list of authors here, you will find Richard Uutmaa and Andres Tolts from the 1960s, but also Olav Maran, or Urmas Pedanik, Peeter Mudist, Malle Leisi, Märt Bormeister, and Kalju Nagel from the 1970s; Toomas Vint, Evald Okas, and Alfred Kongo from the 1980s; Enn Põldroos, Jaan Elken, but also Marko Mäetamm, and others from the 1990s. Siim-Tanel Annus, who rose to prominence in the late 1980s as a revolutionary performance artist, closes the selection with his most recent painting, which bears the significant title Genesis 2023, which Art Historian Heie Marie Treier writes about in the catalogue: ‘What does the word ‘Genesis’ mean? …/the book of Genesis from the Old Testament translated into Estonian. The story of the creation of the world, the story of the Garden of Paradise, the story of a perfect life without evil, and then the story of how a man and a woman were deprived of paradise because they wanted to experience a life of the flesh with suffering and become wise through it. …/.’

From this description, we could take the last strand of thought, as a generalisation, referring to what art refers to – a message that is so important at a particular moment in time that it transcends time, inviting us to reflect on the important aspects of life and the possibility of becoming wiser, better, and more beautiful in spirit. Even if, on this particular occasion, this is the emphasised aim of our art show – to find wisdom through the eloquent world spaces depicted in the picture frames, through each individual work as well as through the word art in the larger whole.

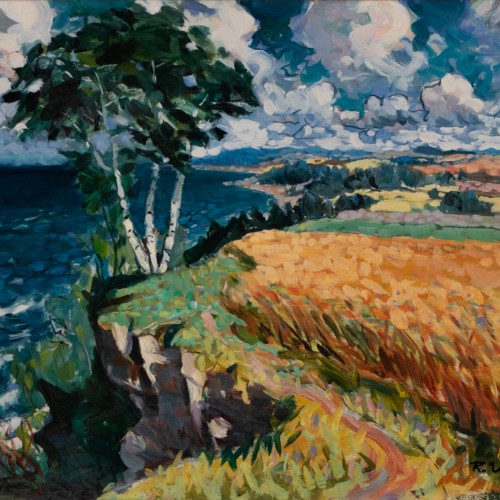

SECOND HALF OF THE 1960s

The 1960s can be seen as a decade of liberation – there was a liberation from the very narrow frameworks that artists were forced into shortly after the war. The year 1966 has been highlighted as particularly groundbreaking in art, when a number of exhibitions of young artists as well as older ones were held in both Tallinn and Tartu, which would have been banned earlier. KUMU has even called 1966 the year of art revolution.

As we know, the liberation here was in sync with the international youth movement (hippies, flower children, oriental spiritual practices), the effects of which, interestingly, also extended beyond the Berlin Wall, the protected and guarded Soviet Union. There were three innovation movements of young artists in art – ANK '64 and SOUP '69 in Tallinn and Visarid in Tartu, which sought synchronisation with the exciting events of their time in elsewhere in the world.

The breakthrough of the 1960s visually looked like abstract art. Abstractionism has had a special place in the conceptualisation of modernist art in general – it has been considered the culmination of modernist art, and here the art of painting was once again leading the way. Abstract art was not taught in school, nor was the history of 20th-century art taught. This was what the artists themselves had to achieve, invent themselves by mutually educating and inspiring each other. So, the aura of forbidden remained attached to it, as the claim of figurative and socio-realist art was still promoted nationally.

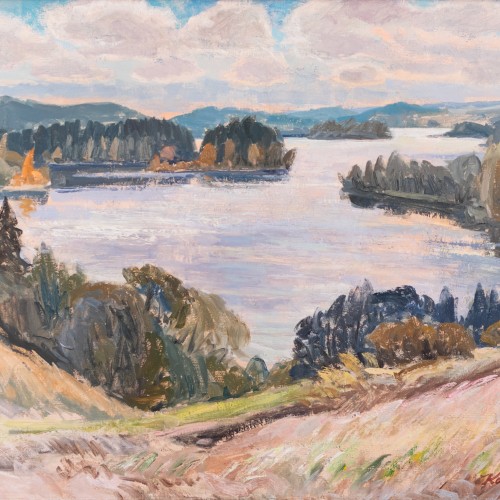

1970s

In Estonia in the 1970s, painting can be broadly divided into two geographical so-called schools, the two largest cities – Tallinn and Tartu, respectively. Already from the end of World War II, art life began to be centralised in Tallinn, or the capital, similar to the Soviet policy of centralising art life in Moscow, i.e. the capital. Apparently, similar tendencies took place in all the Soviet republics.

Although Leonhard Lapin was particularly sarcastic about the spiritual atmosphere of the 1970s, seeing what was done in architecture, when the construction of Lasnamäe began in Tallinn and construction continued in Mustamäe, while Annelinn emerged in Tartu, it can be said in conclusion that at least some kind of progress took place there, and many people were able to feel Soviet luxury for the first time in their lives, i.e. warm water flowed from the tap. The school taught that the Soviet party and the government know exactly in what year the entire Soviet Union will reach communism, hence Estonia. Was that strategic year supposed to be 1975 or 1985, who remembers it anymore. Communism, on the other hand, meant a terrestrial paradise for everyone.

In painting, artistic innovations continued in a milder form than the innovations of the 1960s. Now, at times, they also extended to the older generation of artists, commonly known as traditionalists.

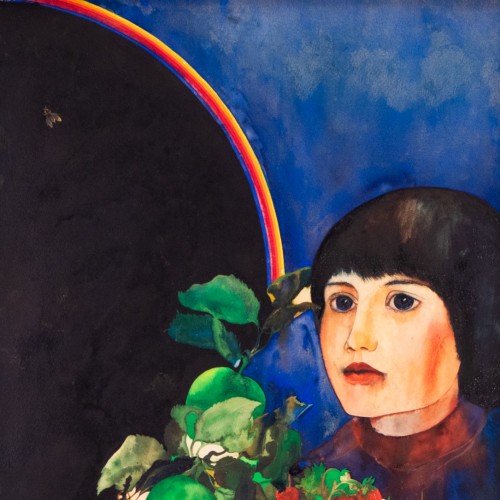

1980s

For painting, the 1980s were especially favourable – by default, painting was considered the absolute pinnacle of the hierarchy of arts, which meant that painters could also feel dignified and respected. It was based on the knowledge that all international modernist art history writing was painting-centric. According to this, innovations and revolutions in the art of painting took place first throughout the centuries, only then passing on to other artistic techniques and fields. Such a model gave confidence.

On the other hand, under the leadership of Karl Vaino and Brezhnev, the 1980s were the most attenuating time in spiritual terms ever. Since there were no more innovations in painting, but the focus was on the endless improvement of the current level, the art innovation was instead transferred to exhibition design, poster, and design, which was considered peripheral areas. In one of his articles, Evi Pihlak, a highly respected art historian at the time, asked the question in the spirit of Arthur Danto: has art now been completed in Estonia as well?

As we know today, the 1980s were, in fact, absolutely groundbreaking in political terms, leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and then to the fall of the Soviet Union. Upheavals began to appear in young Estonian art in 1986, but this is a completely different story.

1990s

In general, exhibitions, museums, and the press focus on the innovations in art of the 1990s and the public’s nervous shocks associated with them, on the young generation of artists of the time, who, as national borders opened up, accepted different influences from the wider world and from Estonia, testing all kinds of boundaries. The KUMU Art Museum has now decided to bring Estonian art from the 1990s into its permanent exhibition, with lots of video and photography and installation and conceptual works made in contemporary technologies. It is worth going to see KUMU’s selection. Today, the shocking artistic innovation of the time has become safe art history.

However, this auction selection from the HAUS Gallery presents a completely different picture of the 1990s – on the one hand, the early student works of the future celebrity and, on the other, the already familiar aesthetics of older artists with established views. Neither side may have gotten into the exhibitions. Thus, such a selection also offers the art historian the wonder that it is possible to curate such a painting-centric art of the 1990s. Apparently, the balanced sight only settles when viewed in the long run.

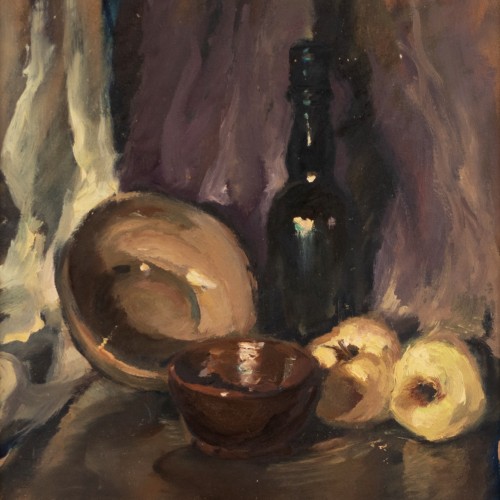

2000s

The addition of the new number to the century and the arrival of the 2000s marked a strange calm in Estonian society and the art world, as if there had been a change in the atmosphere itself. The word ‘normalisation’ has come to be used to describe this, meaning that institutions (especially museums, schools, etc.) were regaining their strength (just before, in the 1990s, there was institutional stagnation). In 2004, Estonia joined the European Union, and in 2006 the KUMU Art Museum was built, which gave a new perspective and acceleration to the art scene. The younger generation of emerging artists had a different attitude from the earlier ones, more introverted, again valuing realistic perfectionism in art. The generation that was exhibiting at the time has not yet brought their works to the HAUS auctions, but that time is probably not far away…

2010s

There was a lot happening on the art front in the 2010s – it was a time of international breakthroughs for younger Estonian art, with photography and installation, even ceramics. Estonia’s cultural policy began to give special support to the internationalisation of art, with the help of new institutions. In 2019, a new decade was ushered in with the opening of the Kai Art Centre and Fotografiska in Tallinn, both of which are a completely new type of institution specialising in contemporary art and photography, with a strong link to the international professional community.

In the 2010s, curators and the young artists themselves began to attract works by artists of an older generation to their exhibitions, mixing the waters in a good way. One of the first strong examples of this was the exhibition of paintings / ceramic installations by Tiit Pääsuke and Kris Lemsalu Kaunitar ja koletis (Beauty and the Beast) at the Art Hall in 2016, initiated by curator Tamara Luuk. This was followed by Kris Lemsalu’s appearance in the Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Authors of works in the HAUS Gallery auction have also collaborated with younger artists. The years of completion of the works here could be considered rather chronological, marking the self-satisfaction and internal evolution of the work.

2020s

The 2020s have only just begun, but each of us already knows what we had to live through from 2021–2022 as the whole world was locked up, and how it has affected our personal lives as well as the wider economy, politics, and culture. Perhaps this has led to greater humility in a good sense? The current younger generation of artists are still learning and we will hear from them in the near future. Where is art going? Exactly in the direction in which society, science, economics, politics, and everything else is going. There could still be surprises here.