Auction > Past > Haus Gallery

Haus Gallery 06.05.2023 13:36

ESTONIAN ART AUCTION - MID-19TH CENTURY TO 1965

SPRING 2023

Saturday, 6th of May

ON A TIMELINE

Foreword: Piia Ausman, Curator of the Auction

Author of the catalogue texts: Eero Epner, Art Historian

The 2023 spring auction organised by Haus Gallery presents art on a timeline. It is important for us to offer systematic and thematically curated selections of works to both auction participants and art lovers. Each auction leaves an art-historical trail, mapping out for the public works that have until now been in private collections, and in some cases completely undiscovered, complementing and illustrating the creative history of many artists. Each of Haus Gallery’s current and subsequent auction exhibitions is not just an event focused on buying and selling works, but aspires to be a biannual small survey exhibition, bringing together a comparative picture of our art’s past, development, experiments, and present.

This year’s auction exhibition will present works throughout Estonian art history, grouped by decade. This catalogue covers the period from the mid-19th century to 1965. It was the 1960s that were the most tumultuous in our art, when both old and new artists visibly mixed. An era when the Pallas artists, who made their mark in the first half of the 20th century, painted alongside the young names who had just emerged on the art scene and who have now become classics of our modern art. So, in this decade, we can see side by side the new world vision of the ANK '64 group and landscapes created in the key of classical modernism, as well as the modern experimental expressions of experienced artists.

Curated in this way, the exhibition certainly creates a truer reflection of reality, showing both the differences and similarities in artistic pursuits at the time, revealing the divisions and commonalities between the eras and the inherent intertwining.

Although, when placed in a logical sequence, the selection of works in Haus Gallery’s art auctions can still be characterised as an overlapping of curated coincidences, a process that is fascinating in its mystery. In most cases, it is impossible for us to plan in advance the works that will be auctioned, as they come from private collections, especially in the case of early art, and the decisions to sell them are often taken outside our control. You could say that the works are finding us and we are looking for the best ways to showcase them. These coincidences are all the more inspiring. Each selection of art assembled at the moment of the auction has its own individual undertone, setting the challenge each time of how to present the selection and how to combine the works together to tell a thoughtful, holistic story of our art history.

The trace of each auction is an art-historical document – a printed catalogue, a video image, an internet record. The way we present our art in the context of an auction, or more broadly, cannot simply be a series of pictures stitched together for sale, but a responsibility to manage our intellectual heritage with dignity. We also need to think about the educational aspect, about how the art information presented through auctions contributes to our artistic awareness and knowledge in the long term.

In this year’s Haus Gallery auction catalogue, you will find chapters by decade that talk about the important and characteristic features of a given period of time, and go on to describe the role of each author in that period, through the work they are auctioning.

This catalogue begins with Johann Köler’s exceptionally masterful and inspiring arrangement of the head of Jesus from the period 1857–1858, pauses in the 1910s through Konrad Mägi’s outstandingly colour-intensive landscape, looks at Nikolai Kull through his painterly self-portrait from the 1920s, takes a look at Johannes Võerahansu’s touching view of the early spring landscape on the eve of war in 1941, or perceives Johannes Greenberg’s profoundly psychological figure compositions from the same place, touches on the repressed and restrained 1950s, when landscapes but also flowers dominated, and concludes with works from the 1960s, when the young Valdur Ohakas painted a vigorous and experimental courtyard in Tallinn’s Old Town, and Elmar Kits a domestic greenhouse with an old woman who exudes the serene wisdom of being in action…

Our art is eloquent and inherently rich. Now that the selections for the art auctions have been compiled once again, let us take some time together to delve into the art as a whole, as well as the meaningful reflections of each individual work.

MID 19th CENTURY

The 19th century is represented in this year’s auction by two portraits of people by Johann Köler and Theodor Albert Sprengel. Köler depicts a man as a god: a magnificent, large-scale arrangement of the head of Christ, which later became the basis for the famous altarpiece in Võnnu Church. Sprengel, on the other hand, has captured a man as a mere human: with encyclopaedic precision he has painted a Hiiumaa farm woman, without forgetting to include the sea and the little boat in the background, as well as the symbols of Hiiumaa. This meticulous attention to the painting of people remains largely a 19th-century phenomenon, as the 20th century saw a much greater interest in landscapes, still-lifes, and other non-human subjects. If a person is allowed on the canvas, it is more of a generalisation and, for example, the realistic and psychological painting of the face is no longer of interest. Why the 19th century turned out to be so man-centred is difficult to speculate. Obviously, art history conventions and teaching principles play a role here.

1910s

The 1910s are represented by two works that are somewhat inversely related. Konrad Mägi, who lived and worked abroad for a long time, is represented this time with a magnificent view of South Estonia, which is unusually experimental and shows us facets of Mägi’s oeuvre that we have so far been able to decide on the basis of a preliminary draft of the same work. At the same time, Ants Murakin is known as an artist who worked mainly in Estonia, but this time it is his sensitive and nuanced watercolour, painted somewhere in Southern Europe. While Murakin is charming in his truthfulness and his special attention to all the obfuscations and colour blurring in reality, Mägi prefers to distance himself from truth and reality. Although he is inspired by his observation of the landscape, he has quickly distanced himself from it and creates a completely sovereign work that rhymes a little with abstractionism. Bold brushstrokes and experimental colour combinations bring us Konrad Mägi, who is once again in search of something new and discovering for himself. His escape from fixity, from stagnation, was constant and programmatic, and for this reason he tried to reinvent himself with almost every painting.

1920s AND 1930s

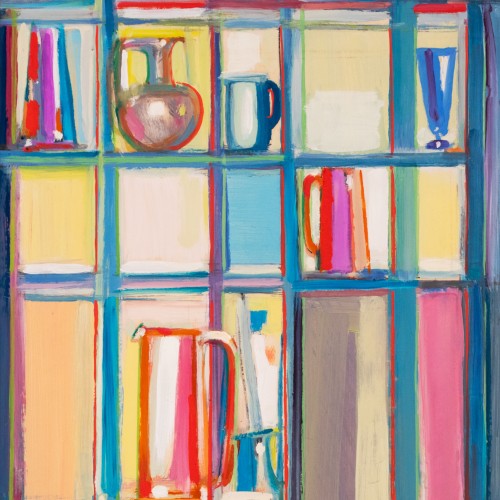

Somewhat surprisingly, the 1920s and 1930s are the most experimental this time. While in general these decades in Estonian art history are known as a period of experimentation and then calming down, in this auction we see five paintings that speak of quite the opposite trend. Paintings by Nikolai Kull and Andrei Jegorov show well-known painters from a new angle. Andrei Jegorov’s painting style, which has already become familiar, will be given a new twist this time through a different composition, an unusual blurring and the introduction of people into the painting. The work of Nikolai Kull is also a true discovery, where Kull, who later became known even for his somewhat robust generalisations, is supple and elegant. From the 1930s, Kaarel Liimandi’s work has been included in this year’s selection. The experiment of one of the most important colour masters in Estonian art history shows him from a new angle and speaks of his unmistakable sense of colour even in the midst of experimentation. Gori’s exploratory watercolour, Erich Pehap’s first known painting, and Ott Kangilaski’s vibrant still-life form an ensemble that speaks of youthful freshness, exploration, and incessant curiosity.

1940s

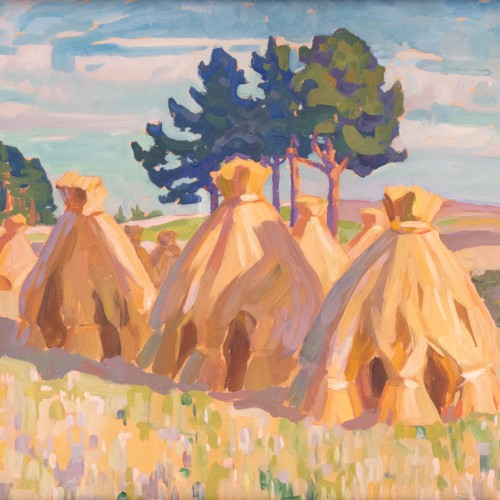

The 1940s were an extremely turbulent and changing time for artists. This is reflected in the current selection, which includes very diverse and fragmented applications. Two paintings by Johannes Greenberg speak most clearly of the more tragic side of the era. Well known to art historians, the works have finally come up for auction and show us a deeply soulful approach to the traumas of the era by a great author. Several authors, on the other hand, delved into quite different motifs: landscapes, haystacks, old town motifs, and so on. By the mid-1940s we already see the introduction of compulsory approaches, but artists still tried to continue with their own: Richard Sagrits chose as his motif the country close to his heart and sought independence with his brushwork, while Nigul Espe depicted the heroic reconstruction of Tartu, but as a man from Tartu he was probably personally interested in this theme. Special mention should be made of Johannes Võerahansu’s masterly portrait of a nurse from the 1940s, which is in keeping with the times, and certainly of the extremely rare early painting by Evald Okas, one of the most versatile and prolific Estonian artists of the 20th century, which is at once filigree in its execution and mysterious in its imagery.

1950s

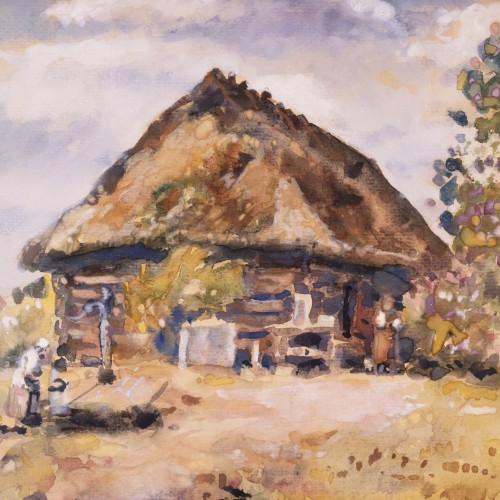

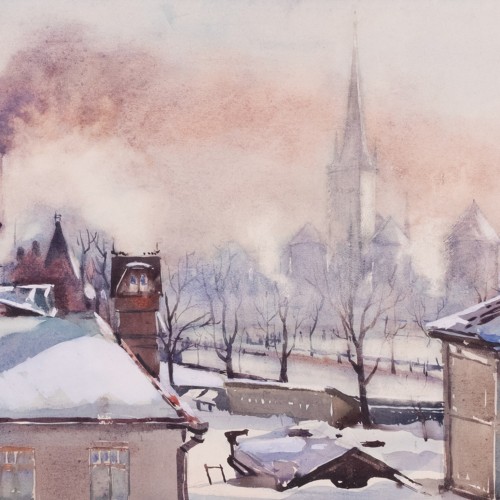

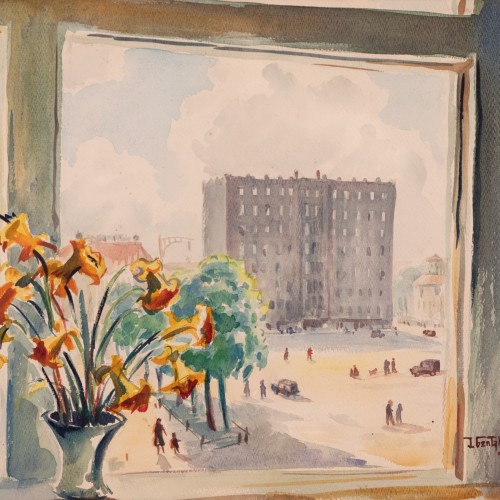

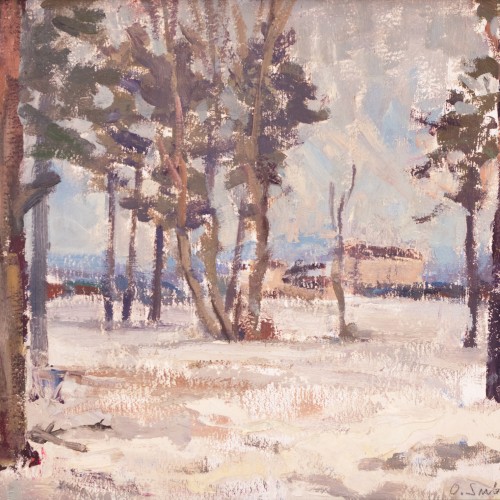

In the 1950s, the branching out of the Estonian art scene deepened, all the more so as many artists were now working abroad. Among them were daring and energetic experimenters, as well as writers who, for years after their departure, painted important motifs from memory. Prominent among these is Julius Gentalen’s airy view of Tallinn, perhaps painted after Stalin’s death, which in its own discreet way celebrates the possibility of a better future. There were also experimenters on this side of the Iron Curtain, but their experiments were rather more cautious due to circumstances: lack of paint, for example, but of course official norms did not allow them to feel so free. All the more admirable, for example, are the experiments of Valdur Ohakas, who tries to achieve the maximum in cramped conditions. On the other hand, there was also quite a lot of focus on tradition and the repetition of archaic life or classical motifs: From Märt Bormeister’s ethnographic view of Kihnu to Johannes Võerahansu’s still-lifes. Lydia Mei’s wistful view of a house in Pääsküla sums up one of the things that characterised the period: finding a sense of security when everything seems to be falling apart.

FIRST HALF OF THE 1960s

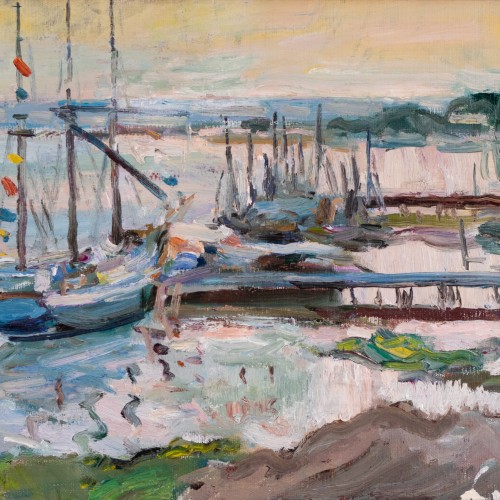

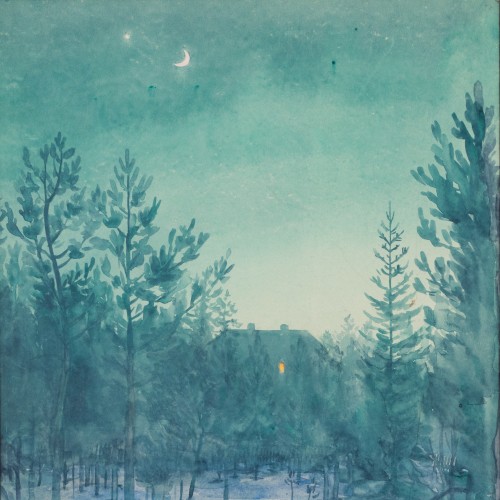

It is well known that the 1960s brought a new wave of searching and a certain liberation. In Estonian art, it was carried by younger artists, such as Jüri Marran, but also by older artists who had graduated from the Pallas school of painting. Elmar Kits and, ten years younger, Henn Roode and Valdur Ohakas were already middle-aged in the 1960s, but that did not stop them from experimenting. Forms faded and spread, colours became bold, motifs became challenging. Even if the subject matter of a painting was classical, a dense brushstroke could turn out to be an unexpectedly bold statement in the 1960s – as Elmar Kits’ painting shows. Henn Roode’s works, however, were a chapter of their own and strongly influenced other artists in pushing their boundaries. Alongside them, however, were authors for whom art was not a platform for searching, but for finding and confirming. The motifs of the homeland in a calm and harmonious combination of colour and light have a special meaning for Richard Uutmaa or Linda Kits-Mägi.