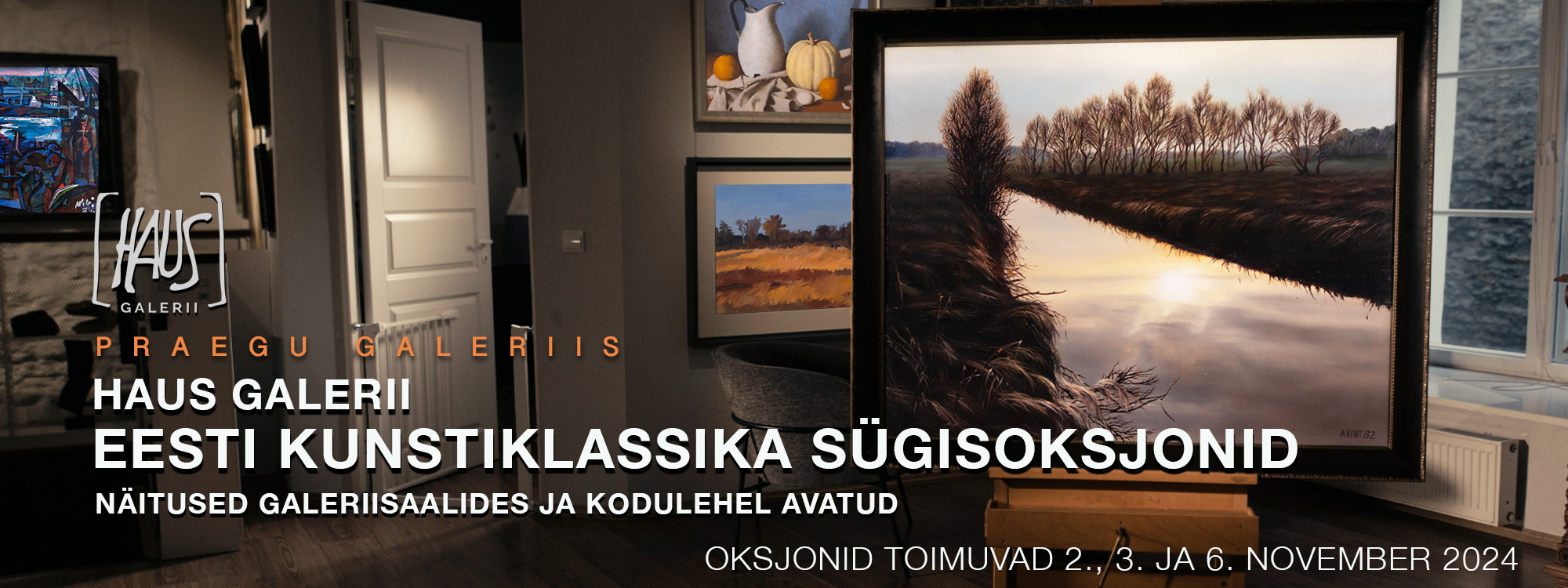

Exhibition > Past > Haus Gallery

Haus Gallery 07.09.2024-05.10.2024

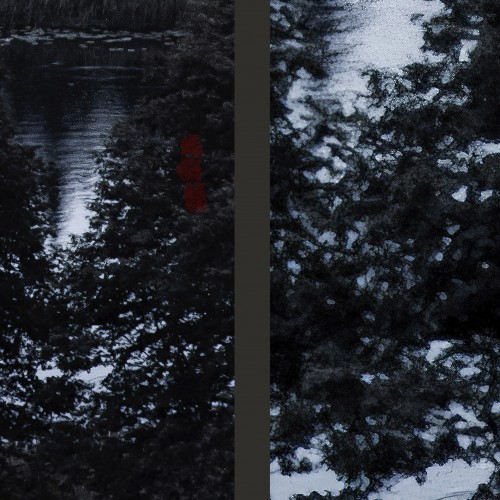

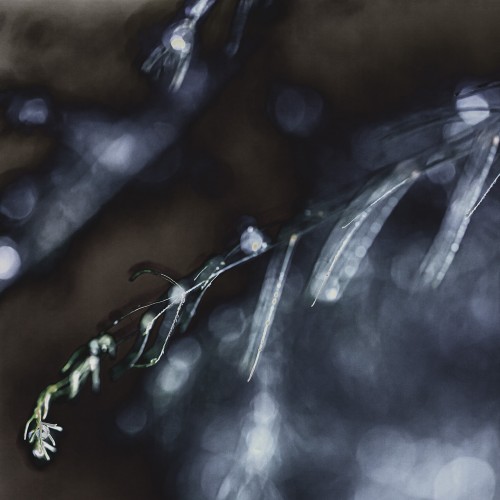

Peeter Laurits, Rein Raud, Märt-Matis Lill

FORGETTING THE SELF

"Forgetting The Self" is an exhibition consisting of pictures by Peeter Laurits, music by Märt-Matis Lille and text by Rein Raua, which is inspired by the teachings and thoughts of the 13th century Japanese Zen thinker Dōgen. According to Dōgen, there is no kind of glorification that a person should strive for while living in this world, because every action that he performs, aware of his participation in the universe, is a form of glorification. Of course, a work of art can also become that. Whether and how Estonian creators have succeeded in this can be seen at Haus Gallery from the 7th of September.

Dōgen (1200-1253) is without doubt one of the most important thinkers in Japanese intellectual history. In 2016, the physicist Adam Frank called him “the greatest philosopher you’ve never heard of” and he may have been right at the time, but meanwhile more and more people have discovered Dōgen, including many of those, who are not engaged in the disciplines of comparative philosophy or Japanese studies at all. Indeed, Dōgen has started to resound not only with people interested in the metaphysics of time and self, but also with those engaged in ecological and post-anthropocentric thought and even management theory. And he has things to say that are relevant for all these areas, and more. At the same time, his ideas continue to be vigorously debated in both academic and Buddhist scholalry circles, since his writings are notoriously difficult and ambiguous. All in all, Dōgen is a major figure in world philosophy who deserves much more attention than he has received up to now. Dōgen was born at a complicated historical moment and in the epicentre of the Japanese culture of the time, as a son of a politically well-connected aristocrat from a family with poetic traditions. He was something of a prodigy and excelled at both traditional learning and literary arts from a very early age, and his relatives hoped he would embark on a career at the imperial court. Nonetheless, the country was torn by civil wars, as samurai clans were fighting for supremacy, and the future of anyone was very uncertain, high-ranking nobility included. Seeing that the sunset of traditional court culture was at hand, Dōgen’s mother insisted on her deathbed that he take monastic vows, and that he did.

Soon enough, Dōgen discovered, however, that Buddhist learning was in a state of decay not unlike the court. His teachers turned out to be unable to support him in his intellectual quest and directed him to another temple, in which a trendy new Chinese import called Chan (or Zen in Japanese) was taught. From there, Dōgen received the advice to go to study in China, but even on the mainland his search continued for about three years, before he settled down with Rujing (1163-1228), a kind, but austere master of the Caodong (Sōtō) lineage, which emphasized simple seated meditation over the cracking of counterintuitive riddles called “public cases”, or kōan, the main instructional tool in the dominant Linji (Rinzai) monasteries.

After two years of study with Rujing, the master acknowledged Dōgen’s englightenment and soon thereafter he returned to Japan, full of hope. What he found was an intellectual scene in turmoil, with various movements vying for the support of powerful sponsors. Dōgen, too, started to look for backing, but though his fame as an accomplished teacher spread quickly, he was evidently not a master of political intrigue, since most appointments and endowments passed him by, even though his community continued to grow. The years in the Kyōto area, when he had still not given up his hopes of making it in the capital, were probably the most productive ones in Dōgen’s life. He was involved in the construction of his own temple and other practical matters on the one hand, and produced many of his finest essays on the other. Still, to his dismay, the authorities held his rivals in higher esteem. Only in 1243 Dōgen finally accepted the offer of a provincial warrior lord to relocate to the North, to the Echizen province (now a part of Fukui prefecture), where a new splendid temple was built for him. Nonetheless, the writings of Dōgen from his last years gradually start to show a bit of resentment and disappointment, and the philosophical vigour gradually recedes. His health, too, started to decline and in 1253, having returned to Kyōto in search of better medical care, he died soon after his arrival.

Among Dōgen’s many works, the central place is held by the Shōbōgenzō, or “The Core Transmission”, written in classical Japanese. The title refers to what Buddha passed on in secret to one of his disciples according to the founding myth of the Chan/Zen school. Many versions exist of this compilation, which contains, in its longest form, 96 essays of varying length, most of which comment on quotes from Buddhist scriptures and sayings by Chinese Chan/Zen masters, from which Dōgen extracts a system of rather extraordinary philosophical insights. Briefly put, the gist of Dōgen’s teaching consists, on the one hand, in the assertion that there is no gap between (Buddhist) practice and enlightenment, and, on the other, that anything one does can be (Buddhist) practice if done in a proper state of mind. “Buddhist” is in brackets here, because it is a potentially exoticizing label and such labels have no meaning. Practice, in other words, does not consist in the enactment of prescribed rituals, pronouncing of formulae or even adopting correct meditation postures, although the latter can be useful as conduits to the enlightened state of mind, which the practitioner can then transfer to all their other activities as well. Notably, for Dōgen, enlightenment is not a threshold, it is not on the other side of a bridge to be crossed, it is a way of being that is fundamentally ours from the very beginning and only needs to be embraced — some other Buddhist schools are with him up to this point — but it can also be exited, for example, when the tax declaration is due and needs to be seen to. The word Dōgen prefers to use instead of “enlightenment” can be more appropriately translated as “acknowledgment” — it is the state of mind in which we are able to acknowledge the entirety of being as it is, and let ourselves be acknowledged by it in turn, with our egos dissolving in it as a result. Reality as such is non-dual, but the label “non-dual” is itself paradoxical, because in order to point to its meaning, it has to make use of precisely the thing that it denies, the concept of binarity or dualism. But if it is something that can be opposed to dualism, then it becomes a part of a binary opposition pair, which is precisely the kind of thing that needs to be left behind.

The system of metaphysics of time, change and process that Dōgen has developed to ground his views is way too complicated to be discussed here in detail, especially as intense discussions are going on regarding its finer points. It doesn’t really help that Dōgen is notoriously subversive in his use of language and treatment of other authors. However, it is certainly fair to say that his thought has anticipated quite a few of the ideas of some late 20th century philosophers, whose names also start with the letter D, and is thus certainly worthy of study, also for contemporary readers, including those who have little or no interest in Zen or Buddhism in general. My translations from the passages of Dōgen’s texts have been lightly modified here for ease of reading.

Rein Raud

Water is not to be found in strong-versus-weak, in wet- versus-dry, in movement-versus-stasis, in cold-versus- hot, in is-versus-isn’t, in deluded-versus-enlightened. When it freezes, it is harder than a diamond — who could break it? When it melts, it is softer than milk — who could break it? While this is so, one should not doubt all its ability of constantly becoming what it is. Think a little: how is it that the water of the whole world can be seen at a particular moment as the water of the whole world? The aim is not to learn how humans and celestials see water. What has to be learned is how water sees water, how water practices water and acknowledges water.

— Landscape as Scripture (Sansuikyō)

When a person achieves enlightenment, it is just as the moon is reflected in the water. The moon does not become wet, the water is not broken into pieces. Even though the reach of moonlight is broad and wide, it can dwell in a tiny drop of water. The whole moon, the entire sky, all contained in a dewdrop on a blade of grass or a drip from an icicle. Enlightenment does not break a person into pieces, just as the moon does not make a hole in the water. A person does not interfere with enlightenment, just as drips and drops do not interfere with the sky and the moon. Deep things have a high reach. As to whether a moment is long or short, you might just as well find out whether “water” is big or small or reach a decision on whether the moonlit sky is broad or narrow.

— The Challenge of Becoming-Immanent (Genjōkōan)

The whole world is a single bright pearl: the whole world is neither big and wide nor ungraspably tiny, neither quadrangular nor circular, it has no centre nor straight lines, it is not dynamically pulsating nor visibly contained in itself. Therefore — and precisely because it does not consist in life-versus-death nor goings-versus-comings — it is life and death, goings and comings. As this is so, it is here that the days of the past converge for departure, it is here where the present moment arrives. If you think this thought to the end: could anyone see this as an assembly of single pieces? is there anyone who can explain this as an indivisible whole? The whole world is an incessant striving to capture things and turn them into selves, to capture the self and turn it into a thing.

— One single bright pearl (Ikka myōju)

All sages are inclined to study how to reach the root by clipping off the entangled vines, what does not happen is the study of clipping entangled vines with entangled vines — they do not know how to entangle vines with entangled vines. Needless to say, they have no clue of how to prolong the entangled vines through entangled vines. Therefore, what is said is nothing but lines from what remains beyond — the teacher and the student share them in the same way. What is heard is nothing but lines from what remains beyond — the teacher and the student share them in the same way. At the bottom of what the teacher and the student share is the entanglement of the Buddhas and predecessors. Another thing to be studied: because the seeds of the entangled vines have the power to leave behind the body, there are branches and leaves, blossoms and fruits embedded in those entangled vines, and as they do or do not branch out further, Buddhas and predecessors become immanent, their challenge becomes immanent.

— Entangled vines (Kattō)

A fish goes through water, but no matter how far it goes, it won’t reach the water’s end. A bird flies through the sky, but no matter how far it flies, it won’t reach the sky’s end. While this is so, the fish and the bird have never left the water and the sky. But although it cannot be said that the fish and the bird do not reach all the limits they have or fail to make their way to all places in their world, if a bird were to leave the sky or a fish leave the water, they would die. You should know: it is through water that fish have life, it is through water that birds have life. It is through birds there’s life, it is through fish there’s life. it is through life there’s birds, it is through life there’s fish.

—The Challenge of Becoming-Immanent (Genjōkōan)

The “I’s” line up and constitute the entire world. One should see every single being, every single thing in it as a moment. Just as different things do not interfere with each other, different moments do not interfere with each other either. This is why the mind arises in the same moment, the moment arises in the same mind. And it is the same with practice and attaining the way. The “I’s” are lined up and each of them sees itself in its own way. This is how the principle of momentary individuality works.

— The Existential moment (Uji)

How the sun, the moon, the stars are seen by people or from the heavens cannot be the same, the perspectives of all kinds of beings are all different. But because this is how it is, whatever is perceived by the mind is on the same footing. All of it is already mind. Should we say that is inside or outside? Should we say it is coming or has gone? Is a drop being added at the moment of birth or not? Is a particle of dust being removed at the moment of death or not? This paradigm of life-vs-death — and the views of it — is there a place where it should be anchored? Eternity is nothing but just one thought- moment of the mind following another.

— Learning with the bodymind (Shinjin gakudō)

To study the way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be acknowledged by the multitude of existents. To be acknowledged by the the multitude of existents is to let the body-mind of the self and the body-mind of others go. The traces

of enlightenment are momentarily paused, and these momentarily paused traces of enlightenment will continue far and wide.

—The Challenge of Becoming-Immanent (Genjōkōan)

The mountains and waters of the absolute present are how the words of ancient buddhas are becoming immanent. Together they abide in their respective configuration, which exhausts their entire potential of becoming. As a message from before the aeon of emptiness, they are the livingness of the absolute present. As particular beings from before any first- person-designation, they are what unleashes the immanence of becoming.

— Landscape as Scripture (Sansuikyō)

Firewood becomes ashes and it cannot become firewood again. Although this is so, we should not see ashes as “after” and firewood as “before”. You should know that firewood abides in the configuration of firewood, for which there is a “before” and “after”. But although there is a “before” and an “after”, both the past and the future are disconnected from the present. Ashes abide in the configuration of ashes, and there is an “after”, and there is a “before”. Just like this firewood, which will not become firewood again after it has become ashes, a human being will not return to life again after death.

Life is a momentary configuration, death is a momentary configuration. This is like winter and spring. One does not say that “winter” has become “spring”, one does not say that “spring” has become “summer”.

—The Challenge of Becoming-Immanent (Genjōkōan)

You should not conceptualize a moment as something that flies by, nor study “flying by” merely as the capacity of a moment. If moments could be fully defined by the capacity to fly by, there would be gaps between them. Who does not accept the discourse of the existential moment is someone concentrating on what is already past. To sum it up: the entirety of existences in the entirety of the world are particular moments next to each other. As existential moments, each of them realizes itself as a “me”.

The existential moment has the quality of shifting. It shifts from what we call “today” into “tomorrow”, it shifts from “today” into “yesterday”, and from “yesterday” into “today” in turn. It shifts from “today” into “today”, it shifts from “tomorrow” into “tomorrow”. This is because shifting is the quality of the momentary.

You should not conceptualize the phenomenon of shifting as the wind and the rain moving from East to West. Nothing in the entire world is ever without movement, is ever without advancing or receding — it is always in shift. This shift is like “spring”, for instance. Spring can have a multitude of appearances, and we call them “shifting”. But you should think about how they shift without involving any external shifter.

— The Existential moment (Uji)

What the stupid scholars really do not understand is that the four great elements that create things and are created themselves, all the particles that jointly make up this world of ours, and, in addition, our ideas of original enlightenment and original essence and the like are all just eye floaters — a disease of the eye. They do not know that the creative power of the four elements exists because of all the particles, nor that relying on those particles this world of ours abides in its patterns — they only see that all the particles are there because of this world of ours. They only understand that eye floaters exist because of the disease of the eye, but they do not grasp the principle that the diseased eye appears because

— Eye Floaters (Kūge)

Maintaining the dynamism lets us see the dynamism that is maintained — this is nothing else than the maintained dynamism of ourselves, right now. This “now” of the maintenance of dynamism is not the original existence or primary ground of the self, the “now” of the maintenance of dynamism is not in its coming and going, its exiting and entering. What we call “the now” does not exist prior to the maintenance of dynamism — it is the immanent becoming of the maintenance of dynamism that we call “the now”. Because this is so, our maintenance of dynamism for this one day is the seed of all Buddhas, the maintenance of the dynamism of all Buddhas. In this maintained dynamism, all Buddhas become visible for us, and their dynamism is being maintained.

— Maintaining the dynamism (Gyōji)