Endel Kõks

(1912–1983)

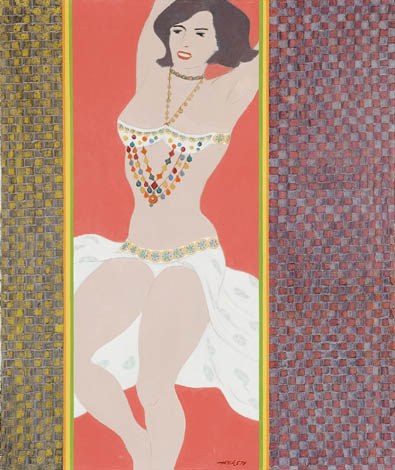

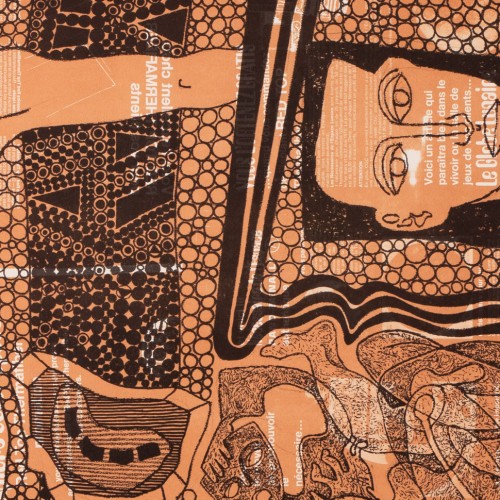

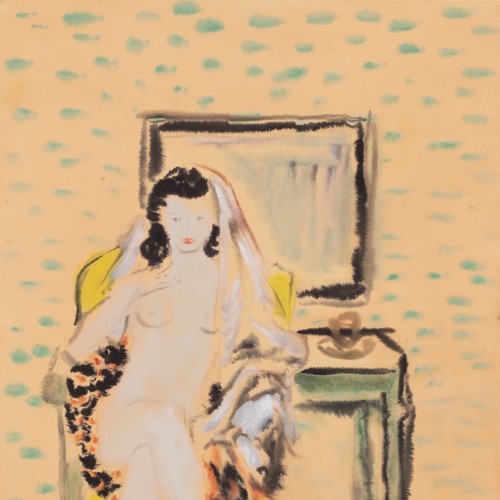

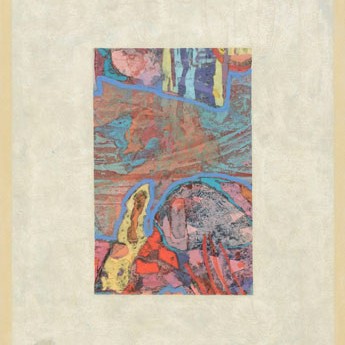

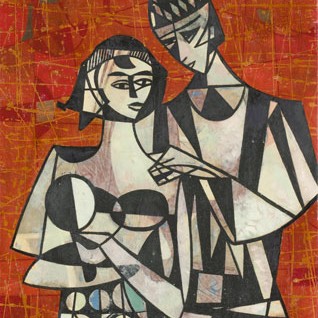

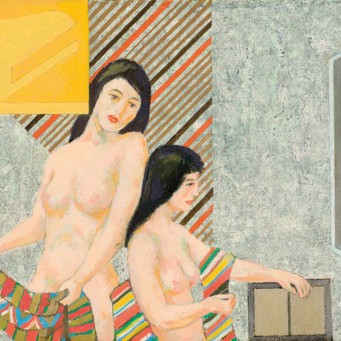

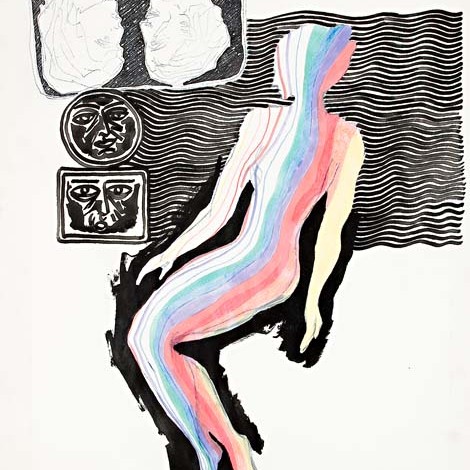

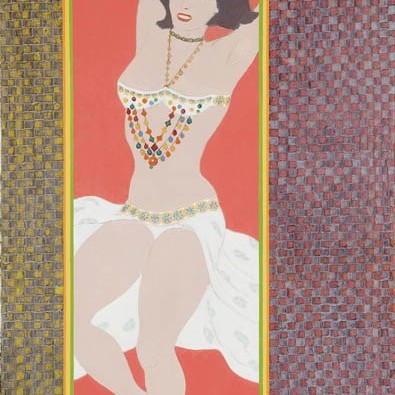

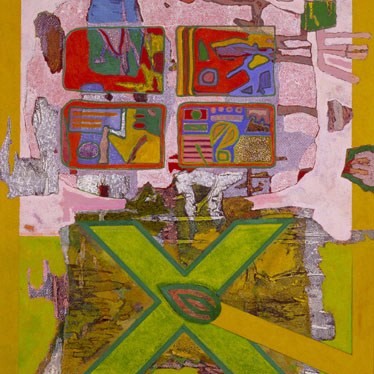

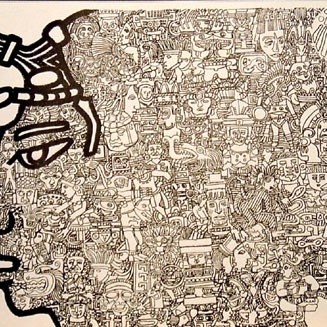

Tantsijanna. 1979

Oil, canvas on cardboard. 91 x 77 cm

price 1 918 (sold)

The Estonian art of painting of the 20.century has inseparably been connected with the local history. This not so much because of the motifs, which have been picked from the social-political context – the “obligatory” themes were implemented in art in a more active manner only in the 1940ies and in the first half of the 1950ies -, but with the shockwaves of historically significant events in private lives and fates of people. This is a century, where especially clearly can be felt the heading of a Peeter Mudist painting “Paratamatus elada ühel ajal” (“Inevitability to live at a certain period”).

So the World War II was one of the most significant events of the Estonian artistic history, the most important result of which was the forced flight of a number of painters abroad. Let us only mention Eduard Wiiralt, Karin Luts, Eduard Ole, Ants Murakin, Eerik Haamer. And Endel Kõks. From here started decades of their ignoring, but not their remaining quiet in the creative sense. Kõks and Luts, Ole and Murakin, Wiiralt and Haamer remained creatively active, in addition to painting they were also able to concentrate on organisational work and to support each other. Even though it seems from here and by using the little information we have got, that the foreign – Estonian circles formed a joint company who rarely looked outside their borders, then it is gradually becoming clearer that leaving was for many artists not taking away of freedom, but creating of freedom. And here in the first range is often mentioned the name of Endel Kõks.

“Endel Kõks is one of the few, who has found in the approximately one century old Estonian figurative art the maximal growth space for his brilliant searching spirit, has reached inexhaustible versatility and a role in the artistic integrity of cultural countries,” writes Vappu Vabar. And really: Kõks, who already received at the end of the 1930ies together with the other members of “Tartu kuldne trio” (“The golden trio of Tartu”), Lepo Mikko and Elmar Kits, the great attention of the artistic public, changed while living in Sweden considerably. In front of him opened the possibilities to breathe in one rhythm with modern trends, not speaking about his trips to the native inhabitants of North- and Latin-America. His extremely elegant taste of colour found now new challenges, which added extreme versatility to his creation. With the example of the present completely different works, we can not grasp all the key words, being characteristic to the creation of Kõks, but we can bring forward the most important ones. At the first glance there exist no joining points between these three pieces, it seems as if their authors are three different persons. But still. It is a justified remark that luckily Kõks was from one side an intellectual and a permanent experimenter, but from another side the basis of his creation was on clear grounds: on the “harmonious sense of colour and plastical sense of form”, being the fundamental truths of the Parisian school (Vappu Vabar).

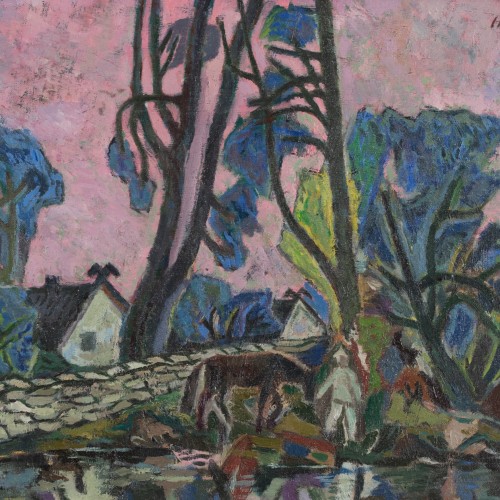

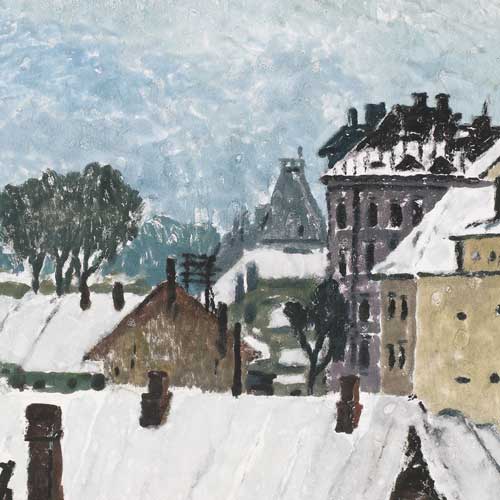

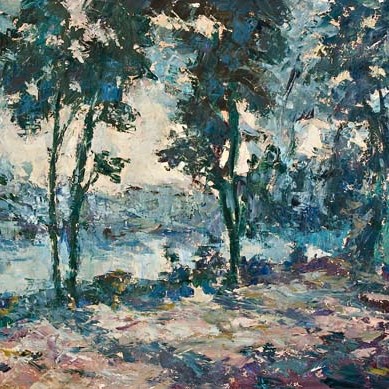

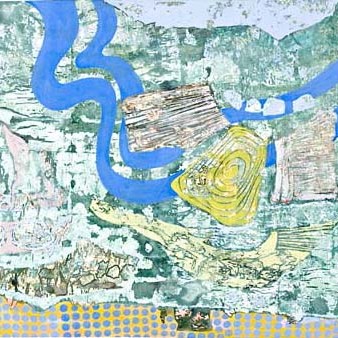

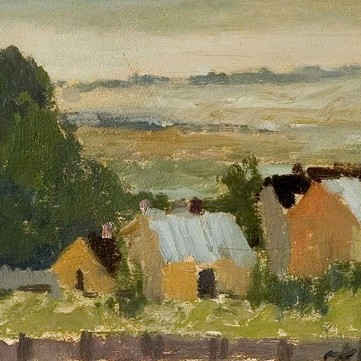

“Maastikuetüüd” shows us the early Kõks. The 30-year-old artist, having graduated from “Pallas” two years prior to the completion of the work, has most probably been wandering near Tartu and has done “fieldwork”. When generally the works by Kõks, originating from the beginning of the 1940ies and the quotations of the classics of modern art, then “Maastikuetüüd” reveals us a totally different Kõks. He is sincere and direct, being able to talk during extremely difficult times of sincerity and stability. Intimate format and subtle colour culture allow to detect the exectness of an already mature artist, the impetuous interpretation of the motif self-assurance, which is connected with maturity. With this work Kõks is standing in a place, where meet traditions and the modern time, classical diving into the landscape and processing of the observed material in a purely personal view.

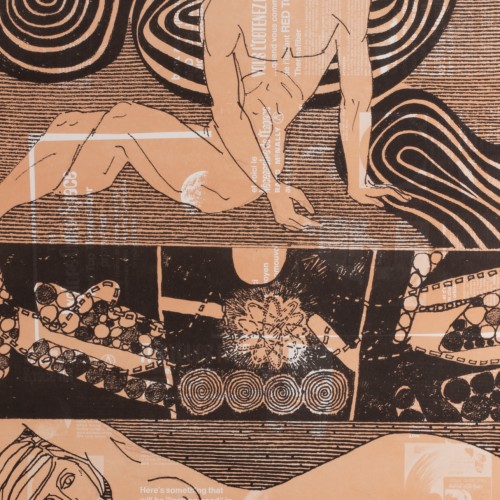

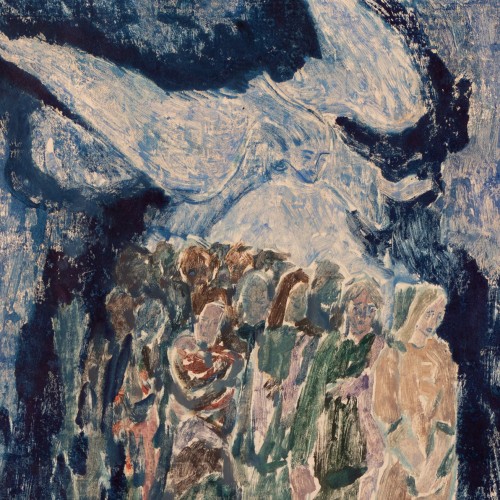

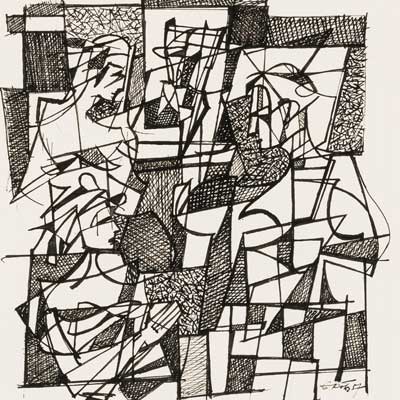

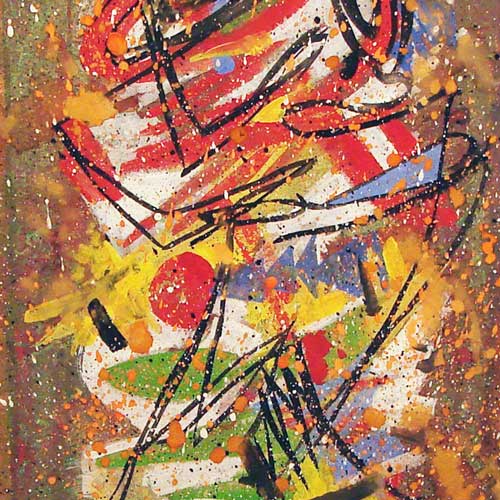

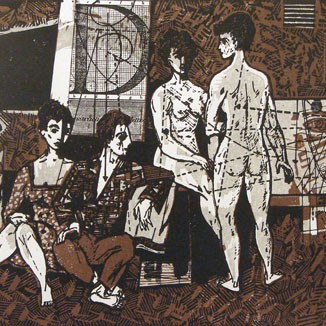

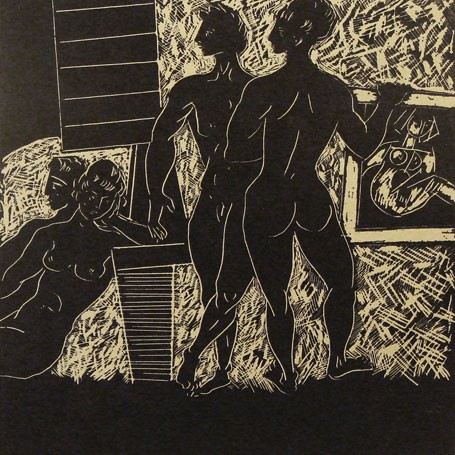

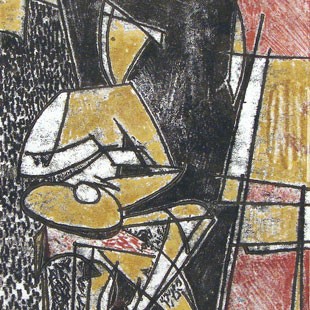

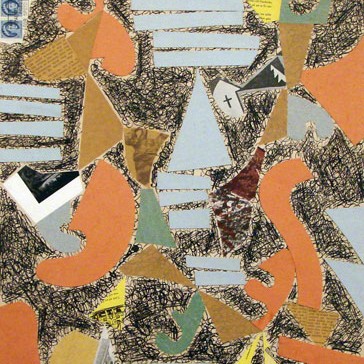

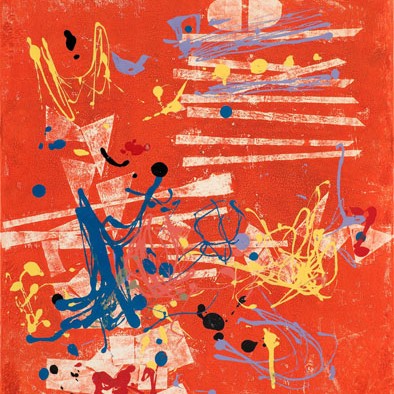

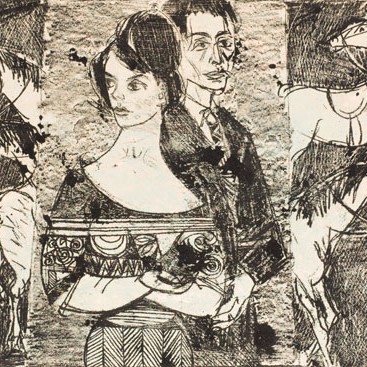

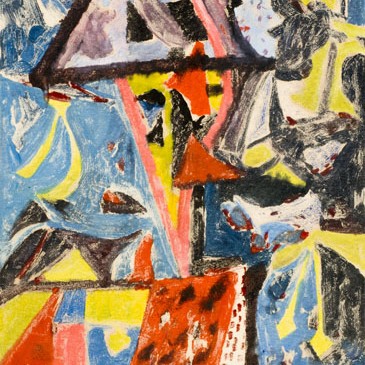

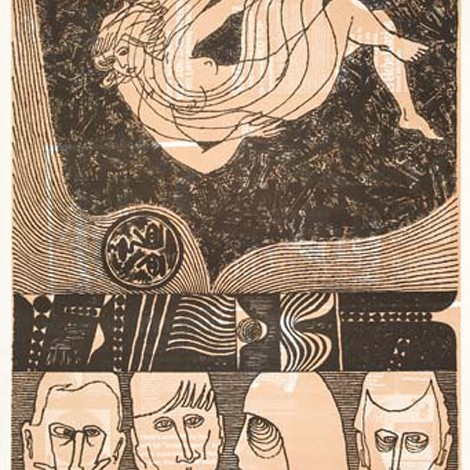

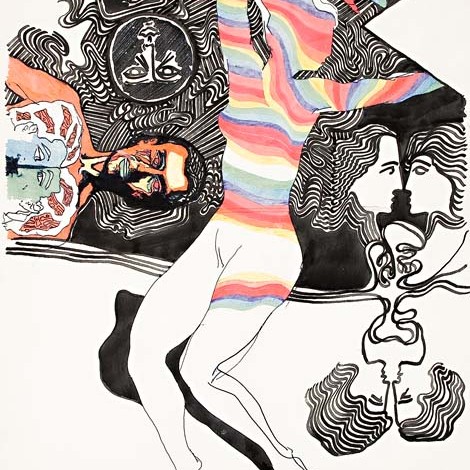

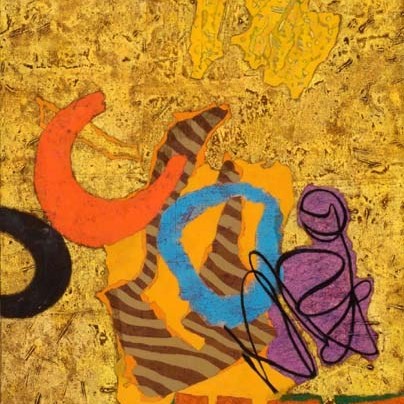

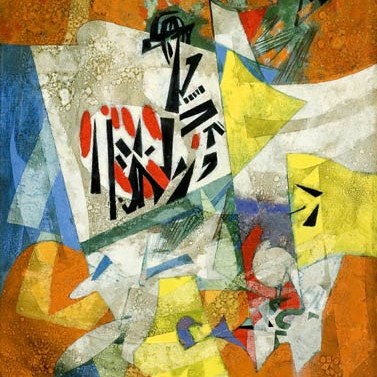

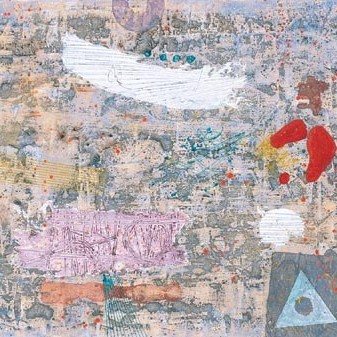

Two years after painting “Maastikuetüüdi”, Kõks first left for Germany, a couple years later already for Sweden, being an active organiser and critic at organising of the foreign Estonian artistic society. Already at his first post-war period we are hit by the first information vacuum, a few examples allow us to talk about the unexpected entering of tragedy and expressionism into his creation. Also the implemented techniques change: to painting is added graphical art. From 1951 Kõks settles down in Örebro, Sweden and restlessness starts to disappear gradually from his works, being replaced by continuous searches. “He becomes a student in the non-figurative class of modern art, where a considerable number of works receive the highest grades,” writes Vappu Vabar, describing well the situation. Artists seldom undertake such considerable changes and step away from the already recognised manner to a completely different one, from figurative art to the abstract one. “Abstraktsioon” (“Abstraction”), having been painted in 1950, is the stylistic example of that period. The extraordinarily strong language of colours accomplishes the susceptible sense of colour, which was acquired in pre-war “Pallas”. Still, Kõks starts to use it totally differently: in spite of depicting something, he concentrates on the actual value of the painting: on colours and forms. Expressionist occasionality and complete freedom of will are here forgotten: Kõks accurately controls the course of accomplishing of the painting, each figure and shade have a concrete place. It is a painting, where abstractionist Kõks has found an elaborate solution to all questions, a complete self-command.

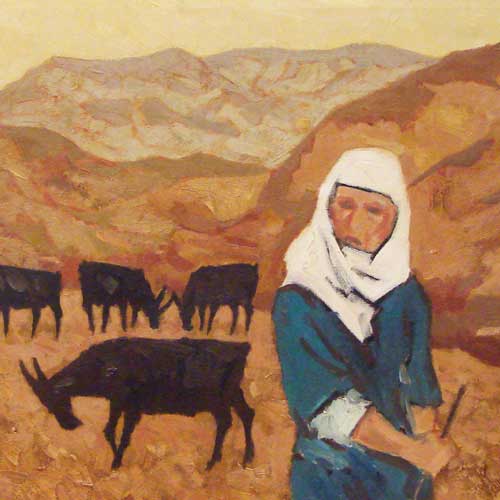

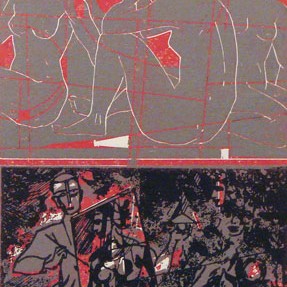

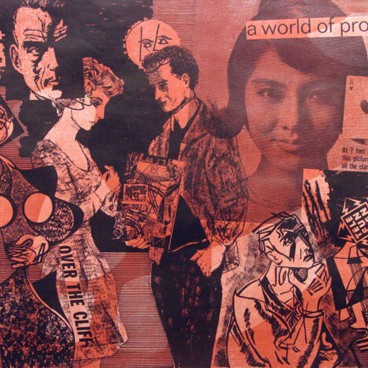

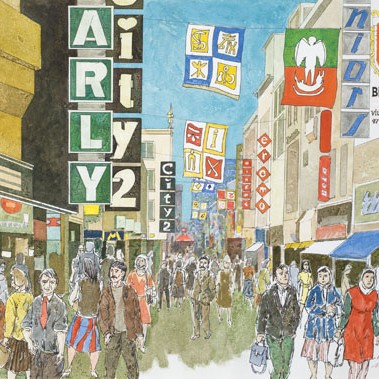

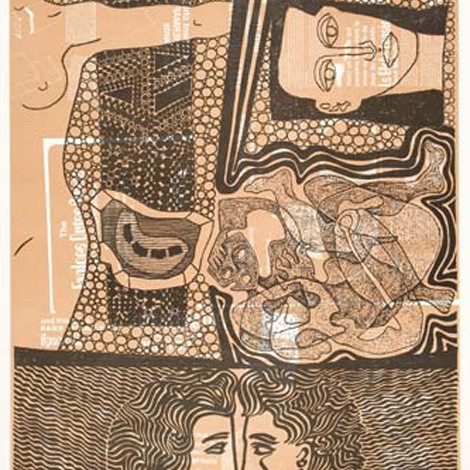

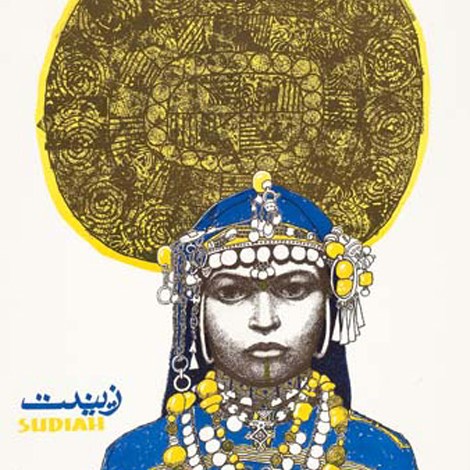

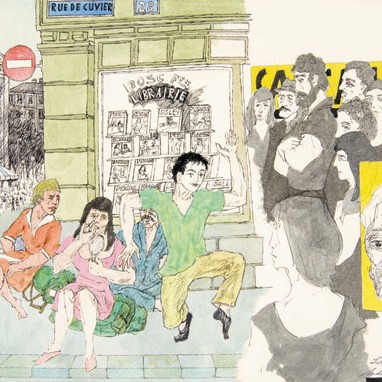

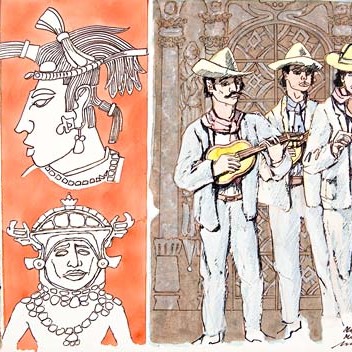

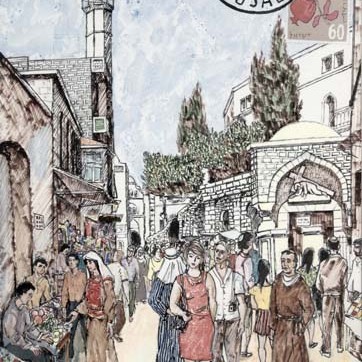

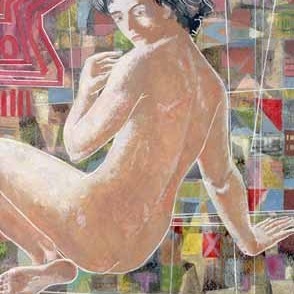

In the year 1967, Kõks made a longer trip to Canada, the USA and Mexico, but the influences of this trip and also of other trips last for years. Graphical works start to include active cityscapes and city clamour, but even more is detected the use of the etnographic materials of the Mexican Indians. Still, “we must say that E.Kõks is first of all a colourist, his originality is expressed in paintings and here says also its words “Pallas” from decades ago””. So it is noticed in man-depicting paintings, how in the works by Kõks always “the colouring is finely tuned” and “the motif spirit is being entered in a sensitive manner”. Unexpected, bright and contrasting colours never leave an over-fastidious impression in case of Kõks, they are always justified. The dancer, having been accomplished in the key of modern art as a model, symbolising the joy of life and optimism, is here framed with patterns, which depict something deeply archaic. And even though at the first glance so different from “Maastikuetüüd”, Kõks has returned to the beginning. The Pallas school of colours and the possibilities to encounter directly modern art indeed brough extremely different paintings to the creation of this “incurable aesthete” (Mai Levin).

Something in common?

The trade mark

“Endel Kõks”.

So the World War II was one of the most significant events of the Estonian artistic history, the most important result of which was the forced flight of a number of painters abroad. Let us only mention Eduard Wiiralt, Karin Luts, Eduard Ole, Ants Murakin, Eerik Haamer. And Endel Kõks. From here started decades of their ignoring, but not their remaining quiet in the creative sense. Kõks and Luts, Ole and Murakin, Wiiralt and Haamer remained creatively active, in addition to painting they were also able to concentrate on organisational work and to support each other. Even though it seems from here and by using the little information we have got, that the foreign – Estonian circles formed a joint company who rarely looked outside their borders, then it is gradually becoming clearer that leaving was for many artists not taking away of freedom, but creating of freedom. And here in the first range is often mentioned the name of Endel Kõks.

“Endel Kõks is one of the few, who has found in the approximately one century old Estonian figurative art the maximal growth space for his brilliant searching spirit, has reached inexhaustible versatility and a role in the artistic integrity of cultural countries,” writes Vappu Vabar. And really: Kõks, who already received at the end of the 1930ies together with the other members of “Tartu kuldne trio” (“The golden trio of Tartu”), Lepo Mikko and Elmar Kits, the great attention of the artistic public, changed while living in Sweden considerably. In front of him opened the possibilities to breathe in one rhythm with modern trends, not speaking about his trips to the native inhabitants of North- and Latin-America. His extremely elegant taste of colour found now new challenges, which added extreme versatility to his creation. With the example of the present completely different works, we can not grasp all the key words, being characteristic to the creation of Kõks, but we can bring forward the most important ones. At the first glance there exist no joining points between these three pieces, it seems as if their authors are three different persons. But still. It is a justified remark that luckily Kõks was from one side an intellectual and a permanent experimenter, but from another side the basis of his creation was on clear grounds: on the “harmonious sense of colour and plastical sense of form”, being the fundamental truths of the Parisian school (Vappu Vabar).

“Maastikuetüüd” shows us the early Kõks. The 30-year-old artist, having graduated from “Pallas” two years prior to the completion of the work, has most probably been wandering near Tartu and has done “fieldwork”. When generally the works by Kõks, originating from the beginning of the 1940ies and the quotations of the classics of modern art, then “Maastikuetüüd” reveals us a totally different Kõks. He is sincere and direct, being able to talk during extremely difficult times of sincerity and stability. Intimate format and subtle colour culture allow to detect the exectness of an already mature artist, the impetuous interpretation of the motif self-assurance, which is connected with maturity. With this work Kõks is standing in a place, where meet traditions and the modern time, classical diving into the landscape and processing of the observed material in a purely personal view.

Two years after painting “Maastikuetüüdi”, Kõks first left for Germany, a couple years later already for Sweden, being an active organiser and critic at organising of the foreign Estonian artistic society. Already at his first post-war period we are hit by the first information vacuum, a few examples allow us to talk about the unexpected entering of tragedy and expressionism into his creation. Also the implemented techniques change: to painting is added graphical art. From 1951 Kõks settles down in Örebro, Sweden and restlessness starts to disappear gradually from his works, being replaced by continuous searches. “He becomes a student in the non-figurative class of modern art, where a considerable number of works receive the highest grades,” writes Vappu Vabar, describing well the situation. Artists seldom undertake such considerable changes and step away from the already recognised manner to a completely different one, from figurative art to the abstract one. “Abstraktsioon” (“Abstraction”), having been painted in 1950, is the stylistic example of that period. The extraordinarily strong language of colours accomplishes the susceptible sense of colour, which was acquired in pre-war “Pallas”. Still, Kõks starts to use it totally differently: in spite of depicting something, he concentrates on the actual value of the painting: on colours and forms. Expressionist occasionality and complete freedom of will are here forgotten: Kõks accurately controls the course of accomplishing of the painting, each figure and shade have a concrete place. It is a painting, where abstractionist Kõks has found an elaborate solution to all questions, a complete self-command.

In the year 1967, Kõks made a longer trip to Canada, the USA and Mexico, but the influences of this trip and also of other trips last for years. Graphical works start to include active cityscapes and city clamour, but even more is detected the use of the etnographic materials of the Mexican Indians. Still, “we must say that E.Kõks is first of all a colourist, his originality is expressed in paintings and here says also its words “Pallas” from decades ago””. So it is noticed in man-depicting paintings, how in the works by Kõks always “the colouring is finely tuned” and “the motif spirit is being entered in a sensitive manner”. Unexpected, bright and contrasting colours never leave an over-fastidious impression in case of Kõks, they are always justified. The dancer, having been accomplished in the key of modern art as a model, symbolising the joy of life and optimism, is here framed with patterns, which depict something deeply archaic. And even though at the first glance so different from “Maastikuetüüd”, Kõks has returned to the beginning. The Pallas school of colours and the possibilities to encounter directly modern art indeed brough extremely different paintings to the creation of this “incurable aesthete” (Mai Levin).

Something in common?

The trade mark

“Endel Kõks”.

Booking and purchase

Appearance in auctions

Exegesis II

1959. Oil, canvas 27.3 x 40.5 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN ART CLASSICS AUCTION: Haus Gallery 04.05.2024

2 300

Final price: 3 200

Flowers on a Dark Red Background

1942. Oil, plywood 41.6 x 34.2 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN ART CLASSICS AUCTION: Haus Gallery 04.05.2024

3 600

Final price: 11 100

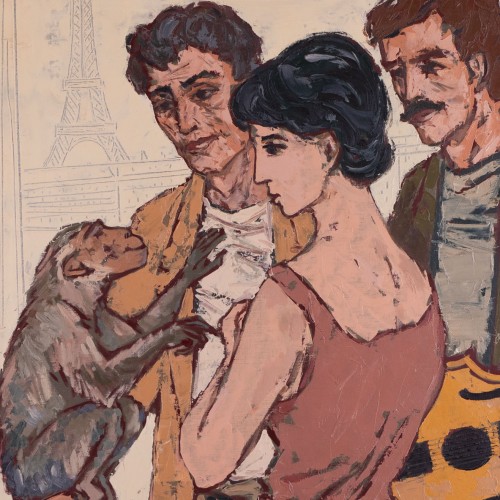

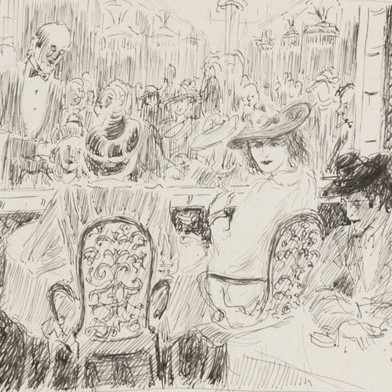

Company in Paris

1965. Oil, canvas 100.5 x 81.5 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN ART CLASSICS AUCTION: Haus Gallery 04.05.2024

12 000

Final price: 25 500

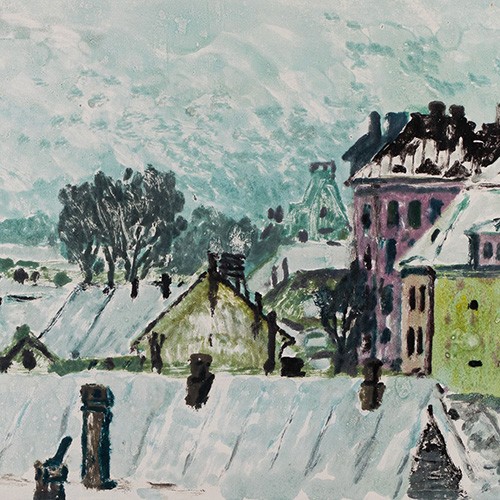

Wintery Cityscape

1944. Monotype Vm 35.6 x 48.3 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN GRAPHICS AUCTION Haus Gallery 08.11.2023

1 400

Final price: 1 500

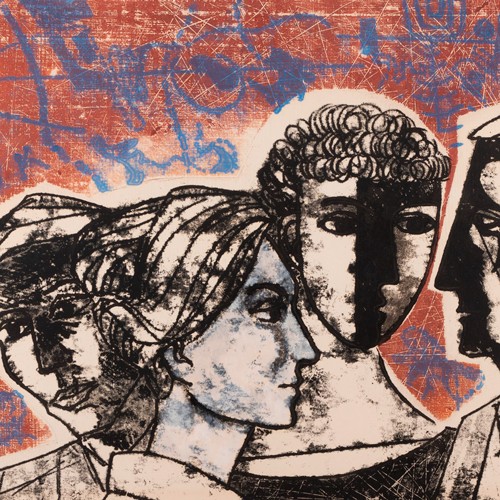

Faces III

1963. Vitreography Km 46 x 55 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN GRAPHICS AUCTION Haus Gallery 08.11.2023

1 800

Final price: 3 400

Rainbow Woman II

1970. Offset lithograph Km 71.7 x 51.8 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN GRAPHICS AUCTION Haus Gallery 08.11.2023

2 300

Final price: 2 500

Flowers

1949. Monotype Vm 47.8 x 39.4 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN GRAPHICS AUCTION Haus Gallery 08.11.2023

2 700

Final price:

Landscape with Figures

1950s. Oil, cardboard 25 x 35 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN ART CLASSICS AUCTION: TIMELESS VISIONS Haus Gallery 04.11.2023

3 100

Final price: 3 100

Flowers on a Green Background

1942. Oil, plywood 48.3 x 38.2 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN ART CLASSICS AUCTION: TIMELESS VISIONS Haus Gallery 04.11.2023

4 100

Final price: 7 200

Wild Horses

1979. Mixed media, paper Km 18 x 24.3 cm (framed)

AUCTION OF ESTONIAN GRAPHICS AND DRAWINGS Haus Gallery 10.05.2023

900

Final price: 2 100

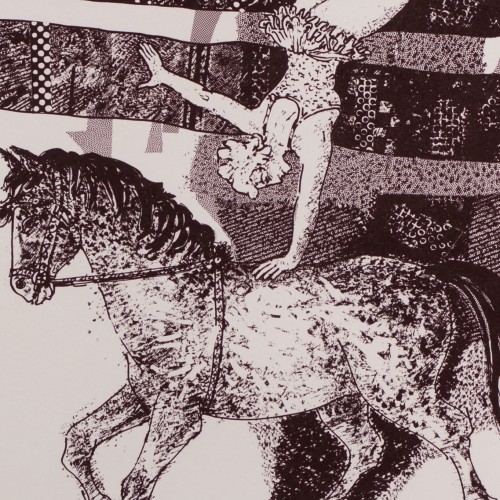

Circus

1972. Offset lithography Km 39.5 x 32.7 cm (framed)

GRAPHIC ART CLASSICS Haus Gallery 03.11.2022

1 200

Final price: 1 200

In the Evening

1958. Gouache, paper 61.4 x 46.4 cm (framed)

EARLIER ART CLASSICS Haus Gallery 29.10.2022

3 100

Final price: 3 100

Mealtime

1954. Oil, canvas 51 x 32 cm (framed)

EARLIER ART CLASSICS Haus Gallery 29.10.2022

4 600

Final price: 7 700

Maybe a Smile

1964. Zink etching Km 36 x 46 cm (framed)

GRAPHICS AND DRAWINGS - Monday, May 16th 18:00 Haus Gallery 16.05.2022

1 100

Final price: 1 700

The Rainbow-Woman III

1970. Offset lithography Km 71.6 x 51.5 cm (framed)

GRAPHICS AND DRAWINGS - Monday, May 16th 18:00 Haus Gallery 16.05.2022

1 300

Final price: 3 800

Woman in Her Boudoir

1979. Watercolour Vm 48.2 x 36 cm (framed)

EARLIER ART CLASSICS - Saturday, May 14th 15:00 Haus Gallery 14.05.2022

1 800

Final price: 2 700

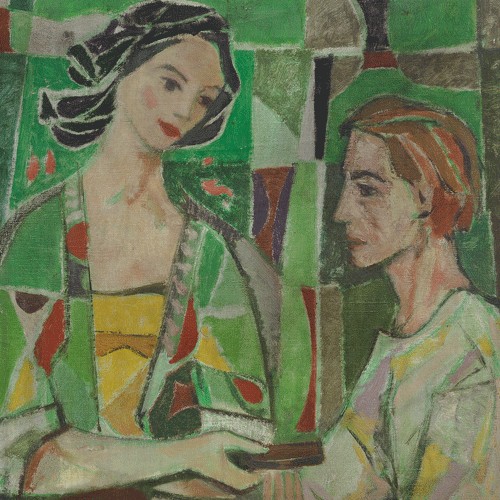

Woman and Man

1954. Gouache, paper Km 63 x 48 cm (framed)

EARLIER ART CLASSICS - Saturday, May 14th 15:00 Haus Gallery 14.05.2022

2 800

Final price: 5 000

Landscape With a Bridge

1950. Oil, canvas 45 x 45.5 cm (framed)

EARLIER ART CLASSICS - Saturday, May 14th 15:00 Haus Gallery 14.05.2022

4 100

Final price: 4 100

Face of a Clown

1956. Monotype Km 46 x 36 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN GRAPHIC ART AND DRAWINGS AUCTION - FALL 2021 Haus Gallery 10.11.2021

1 900

Final price: 2 300

Flowers on the Table

1940. Oil on canvas 79.5 x 70 cm (framed)

ESTONIAN EARLIER ART CLASSICS AUCTION - FALL 2021 Haus Gallery 06.11.2021

6 900

Final price: 7 800

Refugees' Escort

1950. Monotype Km 46 x 38 cm (framed)

EESTI VANEMA KUNSTI KLASSIKA OKSJON Haus Gallery 07.05.2021

1 700

Final price: 2 700

Recital

1941. Oil, plywood 19 x 23 cm (framed)

EESTI VANEMA KUNSTI KLASSIKA OKSJON Haus Gallery 07.05.2021

1 300

Final price: 4 200

Stseen maskidega

1953. linocut 16 x 20 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY'S AUTUMN AUCTION 2019 Haus Gallery 04.10.2019-31.10.2019

700

Final price: 700

Kiirguse valem

1964. Oil, canvas 55.3 x 46 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY'S AUTUMN AUCTION 2019 Haus Gallery 04.10.2019-31.10.2019

4 000

Final price: 4 150

Kaks moosekanti (Pierrot ja Arlekiin)

1950. Oil, masonite 100 x 79.8 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery's Autumn Auction Haus Gallery 01.11.2018

5 600

Final price: 9 500

Seltskond

1957. Ink, paper 19 x 17 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery's spring auction Haus Gallery 27.04.2018

600

Final price: 800

Linnavaade

1944. 35 x 49.3 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery's anniversary auction Haus Gallery 03.11.2017

1 800

Final price: 1 800

Abstraktne

1958. 5 km 47 x 22.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XLI AUCTION. SPRING 2017 Haus Gallery 04.04.2017-30.11.1999

800

Final price:

Juuda kõrbes

1971. 1 43.3 x 60.3 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XLI AUCTION. SPRING 2017 Haus Gallery 04.04.2017-30.11.1999

1 400

Final price: 1 400

Kujundid rohelisel foonil

1960. 5 km 46 x 60.7 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XLI AUCTION. SPRING 2017 Haus Gallery 04.04.2017-30.11.1999

1 500

Final price:

Kompositsioon autoportreega

1969. oil on canvas 112 x 82 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XL AUCTION, AUTUMN 2016. Haus Gallery 28.10.2016

3 100

Final price:

Lilled

1953. mixed media on paper 63 x 49 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XL AUCTION, AUTUMN 2016. Haus Gallery 28.10.2016

2 900

Final price:

Naine peegli ees

1945. oil on paper 43.7 x 37.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXIX AUCTION 2016 spring Haus Gallery 30.03.2016

3 300

Final price:

Abstraktsioon

1960. monotype, mixed media on paper km 46 x 36 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXIX AUCTION 2016 spring Haus Gallery 30.03.2016

1 600

Final price:

Abstrakstsioon sinisega

1964. oil on canvas 136 x 110.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVII AUCTION 2015 SPRING Haus Gallery 06.04.2015

4 000

Final price:

Kuldsarv / Golden Horn

1965-1975. oil on canvas 76 x 55.8 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVII AUCTION 2015 SPRING Haus Gallery 06.04.2015

1 900

Final price:

Delecta

1968. ofset-lito km 17.5 x 25.2 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVI ART AUCTION. 2014 autumn Haus Gallery 06.10.2014

400

Final price:

Her second name

1968. gouache, mixed media on paper lm 55.8 x 75.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVI ART AUCTION. 2014 autumn Haus Gallery 06.10.2014

1 800

Final price:

Maalija/The Painter

1968. ofset-lito km 22 x 13.3 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVI ART AUCTION. 2014 autumn Haus Gallery 06.10.2014

300

Final price:

Theme image

1966. ofset-lito km 17.4 x 14.9 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXXVI ART AUCTION. 2014 autumn Haus Gallery 06.10.2014

300

Final price:

Härjavõitlus

1951. oil on canvas 46.5 x 55 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 25.10.2013

2 500

Final price: 2 500

Kalurid

1943. oil on plywood 48 x 48 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 25.10.2013

3 400

Final price: 3 400

Kunstnik

1955. etching plm 26.5 x 17.5 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 25.10.2013

400

Final price: 725

Merel

1953. linocut km 40 x 39.8 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 28.03.2013

260

Final price:

Fantaasia

1959. mixed media on paper km 46 x 36 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 28.03.2013

660

Final price:

Kohvikus

1945. ink on paper km 12 x 14 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 26.10.2012

390

Final price: 390

Meditatsioon

1957. oil on canvas 60.3 x 40 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 26.10.2012

900

Final price: 3 750

Mees vilepilliga

1956. oil on canvas 55 x 46 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 26.10.2012

1 100

Final price: 3 000

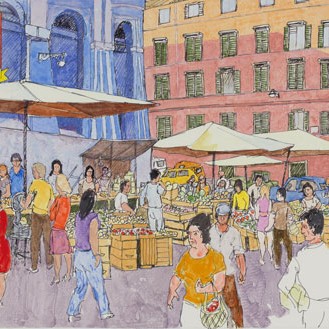

Turg Roomas (Market at Via in Arcione)

1973. mixed media vm 41.5 x 60 cm (framed)

Haus Gallery 26.10.2012

760

Final price:

Tundestruktuurid

1959. oil, mixed media on canvas 71.5 x 23.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXX ART AUCTION 2011 autumn Haus Gallery 14.10.2011

1 620

Final price:

Electronics XXXVI

1963. mixed media km 55 x 46 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXIV ART AUCTION 2009 spring Haus Gallery 28.04.2009

959

Final price:

Linnavaade

1944. monotype km 35 x 49.3 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXIV ART AUCTION 2009 spring Haus Gallery 28.04.2009

959

Final price: 959

Kaks naist

1980. 24 x 33 cm (not framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXII ART AUCTION 2008 spring. Old Masters Paintings Haus Gallery 22.04.2008

895

Final price: 2 301

Mees ja naine

1962. km 35.7 x 45.8 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XXII ART AUCTION 2008 spring. Old Masters Graphics and Drawings Haus Gallery 22.04.2008

575

Final price: 1 118

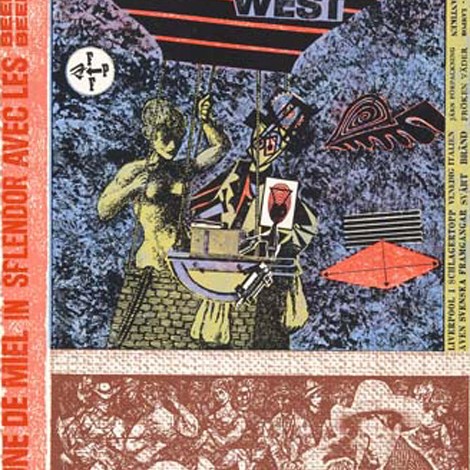

Progressi maailm

1964. etching km 35.9 x 45.8 cm

HAUS GALLERY XXI ART AUCTION 2007 autumn Old Masters Graphics and Drawings Haus Gallery 11.10.2007

575

Final price: 575

Klouni nägu

1956. monotype km 46 x 36 cm

HAUS GALLERY XXI ART AUCTION 2007 autumn Old Masters Graphics and Drawings Haus Gallery 11.10.2007

895

Final price: 895

Varahommikul

1942. Oil, plywood 25 x 28.7 cm (not framed)

HAUS GALLERY XX ART AUCTION, 2007 spring Old Masters Paintings Haus Gallery 15.04.2007-24.04.2007

2 045

Final price: 4 570

Rue Neuve

1979. Ink, water-colour, mixed technique Vm 33.5 x 41.5 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XX ART AUCTION 2007 spring. Old Masters Graphics and Drawings Haus Gallery 15.04.2007-23.04.2007

1 470

Final price:

Westward

1968. Mixed media Km 46 x 34 cm (not framed)

CHARITY ART SALES 2006 Haus Gallery 23.11.2006-20.12.2006

320

Final price:

Rainbow woman I

1970. Lito Km 71 x 51 cm (framed)

CHARITY ART SALES 2006 Haus Gallery 23.11.2006-20.12.2006

447

Final price:

Rainbow woman II

1970. Lito Km 71 x 51 cm

CHARITY ART SALES 2006 Haus Gallery 23.11.2006-20.12.2006

320

Final price:

Maroko

1970. Lito Km 68 x 50 cm (not framed)

CHARITY ART SALES 2006 Haus Gallery 23.11.2006-20.12.2006

383

Final price:

Miim Pariisis

1975. Ink, water-colours Km. 34 x 42 cm

HAUS GALLERY XIX ART AUCTION, 2006 autumn. Old Masters Graphics and Drawings Haus Gallery 24.10.2006

895

Final price: 1 182

Areenil

1958. Water-colours Vm. 44 x 34 cm

HAUS GALLRY XIX ART AUCTION, 2006 autumn. Old Masters Painting Haus Gallery 24.10.2006

1 086

Final price:

Pantheoni ees

1982. Water-colours Lm. 16 x 24 cm

HAUS GALLRY XIX ART AUCTION, 2006 autumn. Old Masters Painting Haus Gallery 24.10.2006

447

Final price: 447

Rainbow-woman I

1970. Ink, coloured pencil, mixed technique Lm. 66 x 51 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIII ART AUCTION, 2006 spring. Old Masters Graphics and Drawing Haus Gallery 20.04.2006

959

Final price: 959

Rainbow-woman II

1970. Ink, coloured pencil, mixed technique Lm. 66 x 51 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIII ART AUCTION, 2006 spring. Old Masters Graphics and Drawing Haus Gallery 20.04.2006

895

Final price: 1 438

Mehhiko muusikud

1972. Felt-tip pen, gouache, mixed technique Vm. 42 x 56 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIII ART AUCTION, 2006 spring. Old Masters Graphics and Drawing Haus Gallery 20.04.2006

895

Final price: 895

Maastik

1944. Oil, veneer 57 x 67 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIII ART AUCTION, 2006 spring. Old Masters Painting Haus Gallery 20.04.2006

3 004

Final price: 4 218

Airscape

1969. Gouache, mixed technique, paper33 53 x 73 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIII ART AUCTION, 2006 spring. Old Masters Painting Haus Gallery 20.04.2006

2 109

Final price:

Olümpiarõngad

1968. Oil on canvas 91 x 78 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XVIIth ART AUCTION, 2005 autumn Haus Gallery 20.10.2005

3 323

Final price: 4 506

Kolm randlast

1943. Oil on paper 35 x 46 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIIth ART AUCTION, 2005 autumn Haus Gallery 20.10.2005

4 090

Final price: 4 090

Vana Jeruusalemm

1971. Watercolor, mixed media, paper Vm. 61 x 47 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIIth ART AUCTION, 2005 autumn Haus Gallery 20.10.2005

1 086

Final price: 2 013

Luurel

1942. Oil on plywood 45 x 28 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIth ART AUCTION, 2005 spring Haus Gallery 25.04.2005

1 726

Final price: 1 726

Sinine abstraktsioon

1959. Oil on canvas 66 x 81 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XVIth ART AUCTION, 2005 spring Haus Gallery 25.04.2005

3 068

Final price: 3 068

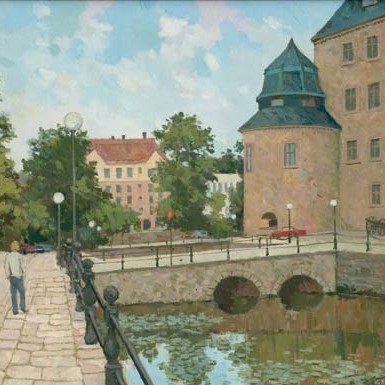

Örebro vaade

1980. Oil on canvas 38 x 46 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVIth ART AUCTION, 2005 spring Haus Gallery 25.04.2005

1 470

Final price: 1 630

Maastikuetüüd

1942. Oil on cardboard 18 x 23 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVth ART AUCTION, 2004 autumn Haus Gallery 21.10.2004

895

Final price: 3 228

Abstraktsioon

1959. Oil on canvas 81 x 65 cm (framed)

HAUS GALLERY XVth ART AUCTION, 2004 autumn Haus Gallery 21.10.2004

2 365

Final price: 4 825

Tantsijanna

1979. Oil, canvas on cardboard 91 x 77 cm

HAUS GALLERY XVth ART AUCTION, 2004 autumn Haus Gallery 21.10.2004

1 917

Final price: 1 917

Rannas

1951. Water-colour Vm. 35 x 45 cm

HAUS GALLERY XIVth ART AUCTION, 2004 spring Haus Gallery 04.04.2004

1 214

Final price:

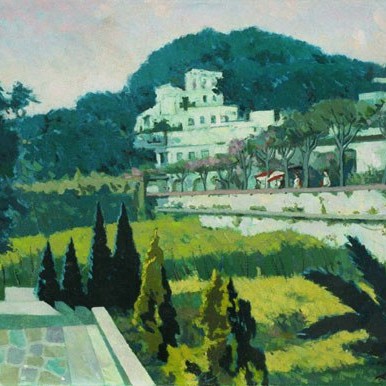

Capri

1982. Oil on canvas 37 x 46 cm

HAUS GALLERY XIIIth ART AUCTION 2003 autumn Haus Gallery 23.10.2003

1 342

Final price: 1 342

Sigma x green

1970. Acrylic, glass fiber fabric 100 x 81 cm

HAUS GALLERY XIIIth ART AUCTION 2003 autumn Haus Gallery 23.10.2003

3 515

Final price:

Kartulivõtjad

1940. Oil on cardboard 37 x 50 cm

HAUS / XIIth AUCTION, 2003 spring Haus Gallery 24.04.2003

2 301

Final price: 2 556

Abstraktne

1959. Mixed media Vm. 59 x 44 cm

HAUS / XIIth AUCTION, 2003 spring Haus Gallery 24.04.2003

1 246

Final price: 1 566

White Memory

1967. Gouache, paper 56 x 76 cm (framed)

HAUS / XI AUCTION, 2002 autumn Haus Gallery 24.10.2002

895

Final price: 1 470

Kompositsioon figuuriga.

1958. 60 x 45 cm

HAUS / IX AUCTION, 2001 autumn Haus Gallery 20.10.2001

1 502

Final price: 1 502

Varahommikul

1942. Oil on cardboard 25 x 28 cm

HAUS / VII AUCTION, 2000 autumn Haus Gallery 26.10.2000

1 214

Final price: 1 694

Lilled

1943. Oil on cardboard 48 x 48 cm

HAUS / VII AUCTION, 2000 autumn Haus Gallery 26.10.2000

1 726

Final price:

Maalijad

1939. Oil on canvas 90 x 99 cm

HAUS / VI AUCTION, 2000 spring Haus Gallery 27.04.2000

3 515

Final price: 5 305

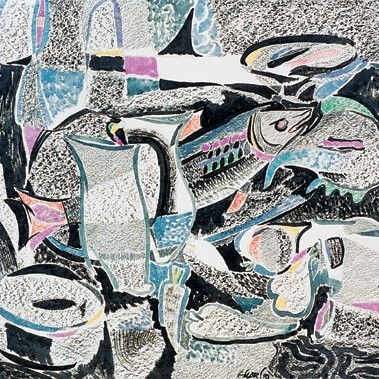

Vaikelu kalaga

1950. kj. 38 x 46 cm

HAUS / V AUCTION, 1999 autumn Haus Gallery 12.10.1999

959

Final price: 959

Bygone Times

1972. Litography 43 x 59 cm

HAUS / IV AUCTION, 1999 spring Haus Gallery 26.04.1999-24.04.1999

511

Final price:

Aias

1943. Oil on cardboard 29 x 29 cm

HAUS / IV AUCTION, 1999 spring Haus Gallery 26.04.1999-24.04.1999

1 853

Final price: