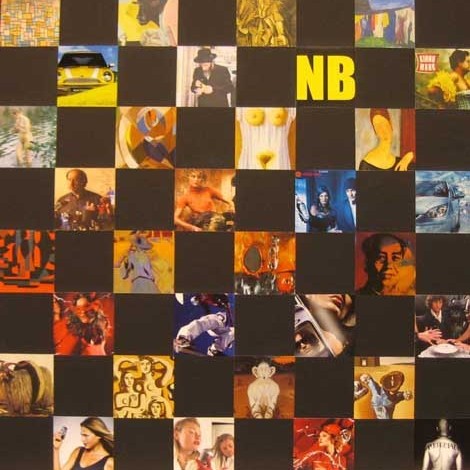

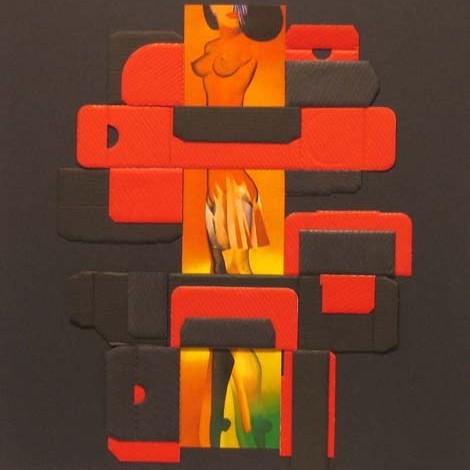

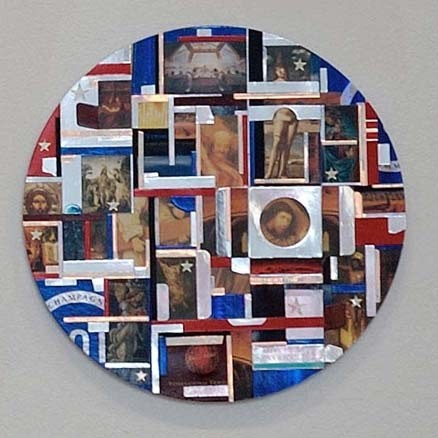

The present exhbition by Leonhard Lapin could be easily interpreted in literary way, as a certain type of special poetry. What I have in mind here, is the construction of his works, the ways that have been used to form the structure of a piece of art and how the author seems to have worked with raw material (reproductions and packages), that are the basis of his works.¹

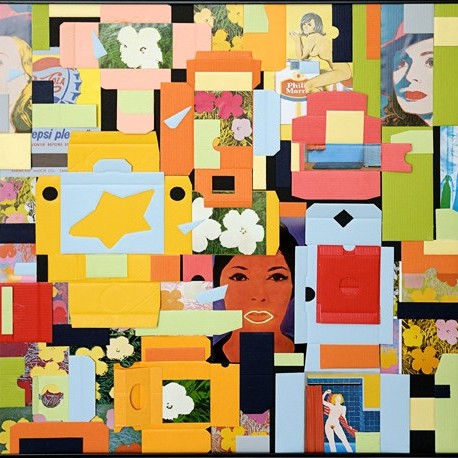

At this point it seems that Lapin, who started with the present series already in 1993 and obviously will go on with it in the future, uses a certain strategy of a double-spy. On one hand, the present series rather organically fuses into “earlier Lapin”, and probably, without being very wrong, we can talk about a constructivist on a from level and ironical attitude towards present day in the semantic field, on saturation of media images and tactics, well-known from pop art where you can regard the art history of entire world as inexhaustible raw material. We can even draw a parallel straight to Lapin\'s first years and to the logo of the art group SOUP \'69. When creating this, the artist interpreted both Campbell\'s tin soup and Andy Warhol\'s interpretation of it. On the other hand, it seems that main key words, standing for Lapin\'s creation, affect only one side. Although such opposition is trivial (and the triviality is the issue Lapin has been trying to reveal all through his creation), we could still say that here a conceptualistic-constructive element has clearly joined associative image logic and extremely subjectivised meaning field. This is the “twilight” zone that everyone, trying to escape from romantic approach to art, righteously avoids, because it does not obey analysis, striving for objectivism.²

That is why the best possible thing to do in this case, is to try and compare structural principles, relying on Lapin\'s perceptive mechanisms, to qualities characteristic to a certain part of poetry. For the writer here, Suprestars series lies somewhere between Charles Baudelaire and Juhan Viiding, reinhabiting 19th century poetry canon, borrowed by the first and following the example of the other, examining rogue\'s use of language.

One of Baudelaire\'s poems in Collection “Flowers of Evil” starts like this:

When in a warm autumn evening, both eyes closed,

I breathe in the warmth of your bosom,

I see happy shores passing by,

that are blinded by monotonous glitter of the Sun; etc.

¹ “Poetry” here should not mean any romantic principle, a general meaning, that has taken over the copyrights of “beautiful”, “sensitive”, “artistic” and still seems to be occupying them. Poetry, in this approach, seems to equal “art”, due to its emphasized use of language and effective images, that certain circles tend to regard the essence of both poetry and, in a wider sense, the whole art.

² Such problematics of twilight areas reflects, through itself, certain unilateralism of art criticism. At the same time I am not aware of many approaches, which, invading twilight areas of strong subjective impulse, could have retained common sense and interestedness, without turning into a critic\'s row of subjective impressions or naïve sighing. Because of that, it is perhaps even better, when reviews rather strive for interpreting conceptual stresses and admit, but do not try to dissect creator\'s positions, relying on emotional perception, included in his works.

¹ “Poetry” here should not mean any romantic principle, a general meaning, that has taken over the copyrights of “beautiful”, “sensitive”, “artistic” and still seems to be occupying them. Poetry, in this approach, seems to equal “art”, due to its emphasized use of language and effective images, that certain circles tend to regard the essence of both poetry and, in a wider sense, the whole art.

² Such problematics of twilight areas reflects, through itself, certain unilateralism of art criticism. At the same time I am not aware of many approaches, which, invading twilight areas of strong subjective impulse, could have retained common sense and interestedness, without turning into a critic\'s row of subjective impressions or naïve sighing. Because of that, it is perhaps even better, when reviews rather strive for interpreting conceptual stresses and admit, but do not try to dissect creator\'s positions, relying on emotional perception, included in his works.

Here we have a rather typical, though unique, example of a poetry canon dating two centuries back. But this is just the area where I can see similarity on principle with Lapin\'s visual rhymes. When Baudelaire announces objective reality in his poem\'s first lines – the evening is warm, eyes are closed, you can smell the breath of warm bosom – then the rest of the poem poetically describes a line of associations that has struck the author. This tradition of beautiful symbols differs from Lapin\'s collages, assembled on visual principle, only to the extent that Lapin does not try to be too “emphasized” in his choice of images, sensitive and aspiring the romanticised side of art.

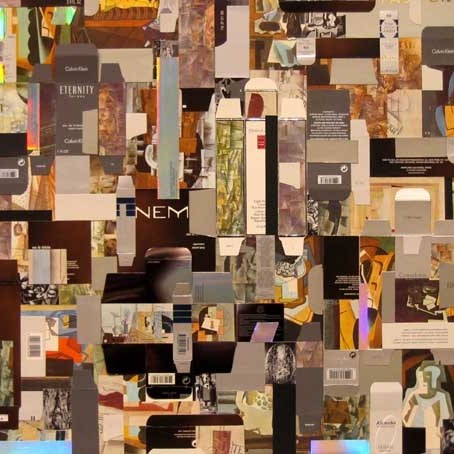

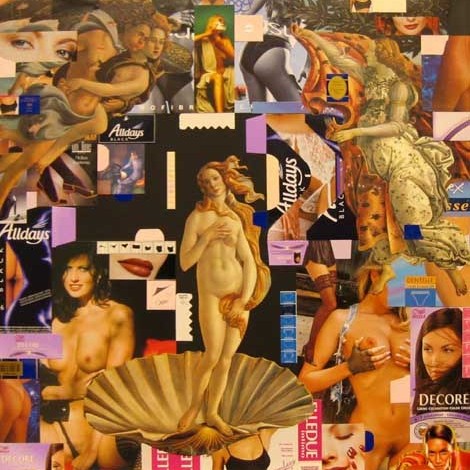

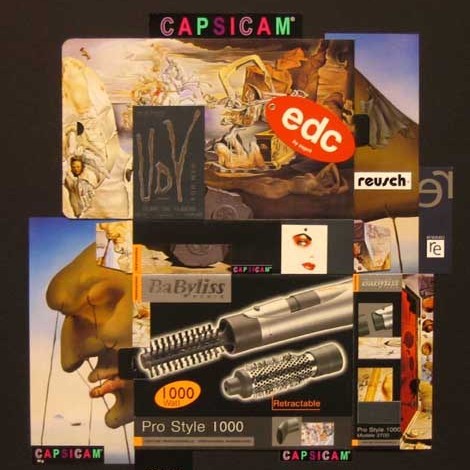

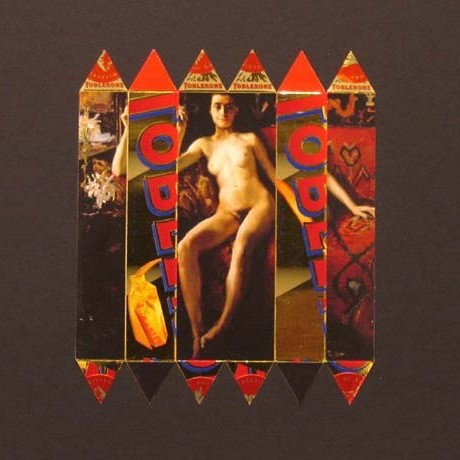

His method rather seems to be a mixture of surrealists\' and pop art, reminding in fact, as an analogue from local art history, of two photographers: Peeter Laurits\' series Fables and Herkki-Erich Merila\'s series Bleu. Although Lapin also proceeds from objects, locating in objective reality, he would rather find his inspiration in culture in its wholeness and diversity. Trash and pornograpfic shots, repros from art classics, perfume wraps, religious images, secret symbols of Freemasons and Kennedy\'s portrait are equal raw material for him. Clearer tactics for pop art would be difficult to invent. But this conceptual attitude, attached to pop art, comes clear especially in the semantic field of his works, on their semantic side, when Kennedy\'s portrait enters into a recognisably poppy happy environment, thus reflecting semantic situation of the 60ies. The same applies to Botticelli, whose Birth of Venus has been exhibited together with soft porn shots.

What concerns formal construction, Lapin rather follows surreal methods, placing considerably big amount of trust in the method of free associations. Throughout times this methodology has brought along formal innovations, which today have lost their actuality, but also truly exciting language findings. In latter cases, language does not achieve to discover or hit the essence of phenomena, which perhaps Baudelaire tried to do, but rather deals with itself and its own ways of usage. Such logic, which allows to draw a parallel with Laaban, perhaps, is seemingly used by Lapin, too. The language he speaks or, in this case, images, which he combines, do not aspire to fix meanings. Suprestars is actually a line of associative visual rhymes that reflects certain qualities, used to create rhymes. This, in its own way, means without doubt playfulness – lightness, when combining and reinterpreting various symbols.

Attraction of Suprestars could be limited to respect of Lapin\'s manual skills. The ways he has combined some collages are visually very effective and inspiring. However, on the other hand, Lapin\'s series seems to attract with eternal avoidance of definitions. When we call this series conceptual-ironic, we obviously do not lie, but we definitely lack something. And again, if we say this is just a row of clearly subjective associations, we evidently do not follow the right path. Nevertheless, it shows, (and seems, is perceptible, can be guessed) that Lapin is different this time. Perhaps even more personal than ever before.

.png)